Caste is a system that organizes people into a rigid hierarchy based on their perceived social status. Historical markers in your community can play an unseen role in perpetuating this system by glorifying and memorializing figures who uphold caste-based ideals. This idea of caste has affected many parts of communities, including how we remember the past. When you look more closely at historical markers, which are put up to remember important events, people, or places, you can see a strong link between these public memorials and the caste system explored in the film Origin.

Caste is a system that organizes people into a rigid hierarchy based on their perceived social status. Historical markers in your community can play an unseen role in perpetuating this system by glorifying and memorializing figures who uphold caste-based ideals. This idea of caste has affected many parts of communities, including how we remember the past. When you look more closely at historical markers, which are put up to remember important events, people, or places, you can see a strong link between these public memorials and the caste system explored in the film Origin.

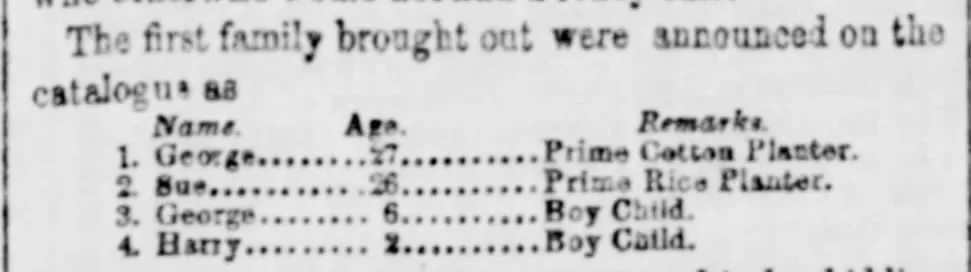

Torrential rain greeted a crowd at Savannah, Georgia’s Ten Broeck Race Course on March 1, 1859. Those invited arrived with money in hand, anxious and willing to weather a literal storm in order to purchase one or more of the 436 men, women and children, including 30 babies, offered for sale. Known today as “the weeping time,” this cruel example of human trafficking that took place over two days would become the largest slave auction in the history of the United States.

Nearly 150 years later, the city of Savannah and state of Georgia have (finally) publicly acknowledged the sale, commemorating it with a historical marker that reads in part, “To satisfy his creditors, Pierce M. Butler sold 436 men, women, and children from his Butler Island and Hampton plantations near Darien, Georgia.”

While it took generations of lobbying, petitioning and negotiating before recognition was granted to the enslaved victims of the weeping time, on the nearby Butler Island rice plantation, where the enslaved had been forced to work and live, the state of Georgia erected a historical marker in 1957. However, it bears no mention of the 1,000 souls who were enslaved in horrendous conditions on the land, nor any acknowledgment of the contributions they made to making the plantation one of the most profitable in the state. That marker simply reads, “Famous rice Plantation of the 19th century, owned by Pierce Butler of Philadelphia. A system of dikes and canals for the cultivation of rice, installed by engineers from Holland, is still in evidence in the old fields, and has been used as a pattern for similar operations in recent years. During a visit here with her husband in 1839-40, Pierce Butler’s wife, the brilliant English actress, Fannie Kemble, wrote her ‘Journal of a Residence On A Georgia Plantation,’ which is said to have influenced England against the Confederacy.”

Photographed By David Seibert, January 20, 2009

While additional markers have been erected over the last decade to honor the enslaved and a robust movement for a larger commemoration continues in the city, the stark contrast between the original marker and the subsequent markers are clear examples of how caste intersects with the teaching of historical facts.

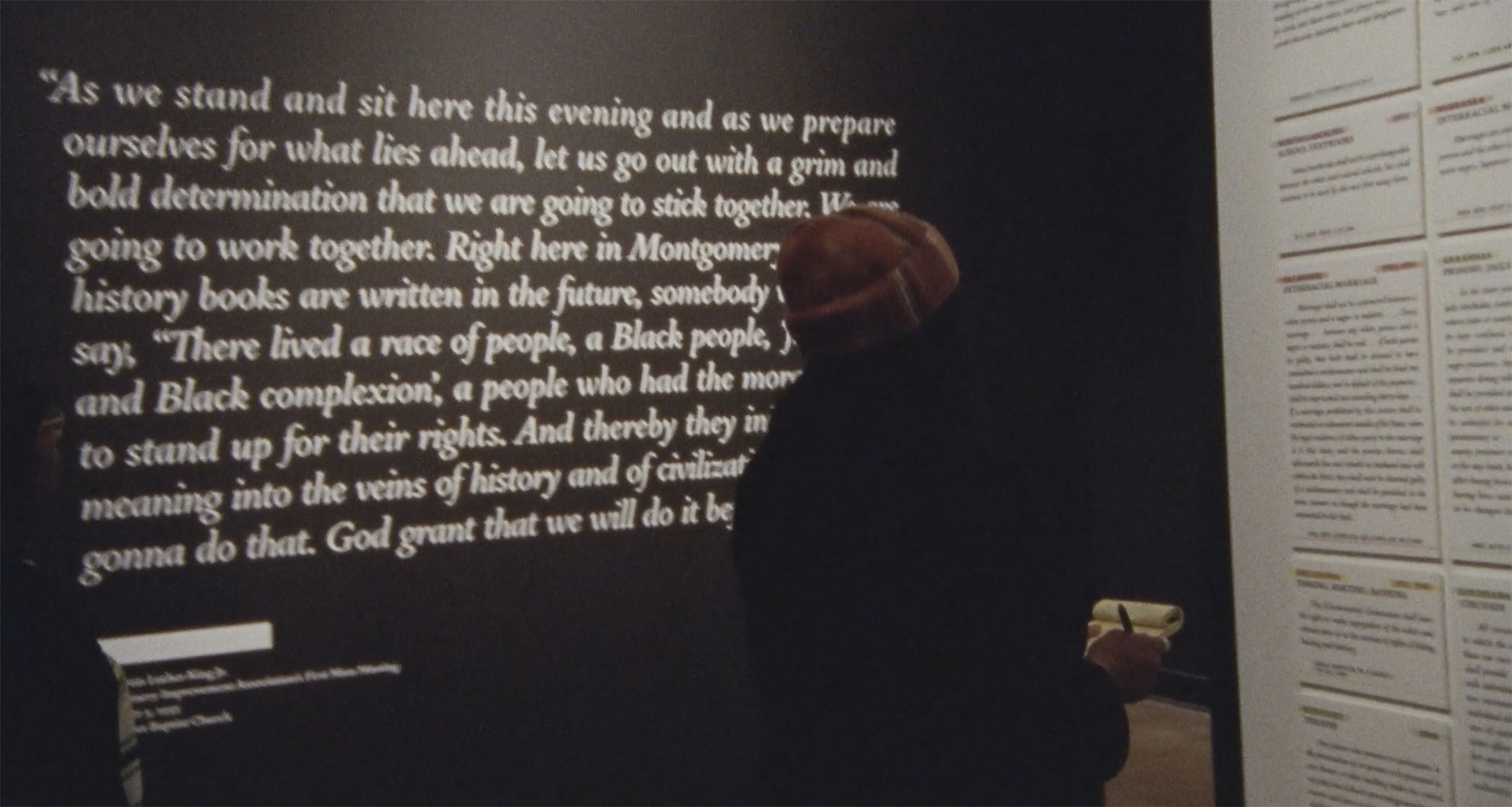

For generations, only one story was told, and it was told through the lens of those in power. It’s time to re-tell the story of your community in a way that amplifies and celebrates EVERYONE who contributed to building it.

PAUSE AND REFLECT

In a city known for its dedication to protecting and celebrating historical spaces, it took more than 150 years to erect a monument to the largest slave sale in the history of the United States. What reasons may have caused the delay?

Annotation as Activism

Annotation is the grammatical art of modifying text to gain a better understanding. Let’s say you are reading a book about gardening. You might make notes in the margins such as “would work well in the backyard” or “only plant in April.” Your notes contain additional information that gives context to what you are reading. The annotations could go as far as to question or correct something the author has written.

In this activity, participants will visit (in person) or find (online) historical markers in their community, create notes expanding upon the information in the marker, and add their voices to the historical dialogue happening all around them.

PROCEDURE

Collaborative Revision of Historical Markers

Let’s annotate! You see a sign in your neighborhood, perhaps at a park, by the side of the road or on the wall of a building, that marks a historical location, but you know the information on the marker doesn’t tell the whole story and misrepresents the past. What do you do next? How can you update a historical marker? You wonder what you can do to speak up against these ideas that have already been designated as history. But you know that these markers, even if written in stone, are part of an ongoing discussion that you can contribute to through annotation.

Use this activity to practice your annotation skills and contribute to your community’s history.

Want to practice annotation before getting started? Take a look at this example of annotation from the National Writing Project, where participants were asked to read an article and leave annotations in the margin.

STEP-BY-STEP

WATCH this video:

- What two events did the video highlight in the city of Dallas, Texas?

- How are the events connected?

- Why is the marker important?

EXPLORE Historical Markers in Your Neighborhood

- Visit the website for Database of Historical Markers (Historical Markers Near You). This is a database that allows you to search markers throughout the United States, including in your own community.

- For this project, you can use the historical markers you find online or visit one in person. Plan a trip to visit a few that are closest to you. If you are unable to physically visit the historical markers, you can download images of the markers from the online database.

VISIT (or view) the historical markers and take pictures of places embedded or carved with words and information.

- As you visit or review the sites, Take notes based on the questions below:

- Location: Where is this marker located? What state? What part of the state? Is the marker near any other landmarks? What is the weather like there? Why might we need to consider the weather?

- Audience: Who is likely to visit this area? Who will read this marker? (For example, age, nationality, education, etc.) Who do you think would not visit this area?

- Purpose: What does the marker want the reader to know? List at least three items, then rank them in order from most important to least important. Is there anything you think the marker does not include that it should?

- Language/Word Choice: What kinds of words does the marker use? Are there any words you do not know or that are confusing to you? Does the marker have words written in a language other than English? Why is this important to think about?

- Credibility: Who created the marker? Does it name an author or a group/organization that created or funded it? Why is this important to consider? Are there any errors you notice on the marker?

- After taking thorough notes, come up with a series of follow-up questions you still have about the marker.

GATHER further information about the historical markers.

- Answering your follow-up questions about the historical site may require you to go beyond your regular online searching and into historical research.

- The first step is forming a research question that can lead you to the archival sources where historical information is stored. To form your research question, follow the below steps from this helpful guide:

- Find/Create a Claim

- Narrow Your Topic

- 1) I am researching ________________________ (topic)

- 2) because I want to find out _____________ (issue/question)

- 3) in order to _______________ (why/purpose/result of project).

- Online archives offer a robust selection of research resources, and you can access many of them for free through your local library. The scope of these archives can be overwhelming, even as their collections are incomplete. If you have trouble finding the information you’re looking for, don’t worry! Unanswered questions are still valuable parts of any annotation.

SHARE your annotation with your community locally and online!

- History is a collective process, so it always helps to get others involved. Including a friend in your annotation activity can offer a new perspective and a helping hand. Talking to a librarian can be an invaluable step toward accessing and understanding research materials.

- Annotation is for everybody! Read these articles about readers and writers who have come together to affect positive change by sharing their annotations. What different forms could your annotation take? How will your annotations inspire the next person who comes across them?

TITLE

In ??? a plaque was erected, after much controversy, in Greensboro, North Carolina to acknowledge There have been debates over the wording of the monument, whether it should

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What did you learn through the process of making your annotation?

- Does updating or revisiting sensitive historic information harm communities more than it helps?

- How should the erection of monuments and remembrances in your neighborhood be decided?

- There are costs associated with creating public monuments, who should be responsible for paying for the plaque? How did you come to your conclusion?