When people think about places that value the practice of free speech and freedom of expression, the United States typically comes to mind. After all, the “Star-Spangled Banner” ends with the words “O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave,” and America has been referred to as a beacon of hope, opportunity and freedom by many.

In this lesson, students will explore the impact of censorship and the significance of symbols in reflecting and questioning cultural and political beliefs.

When people think about places that value the practice of free speech and freedom of expression, the United States typically comes to mind. After all, the “Star-Spangled Banner” ends with the words “O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave," and America has been referred to as a beacon of hope, opportunity and freedom by many.

In this lesson, students will explore the impact of censorship and the significance of symbols in reflecting and questioning cultural and political beliefs.

Lesson Three

Objectives

By the end of the lesson,

participants will be able to:

- Track the banning of a book title in 2024 using a timeline created from articles, videos and state laws.

- Examine the motivations behind book burnings and bannings, including the desire to maintain power, suppress dissent and control information.

- Appreciate the power of symbols across cultures and communities.

- Identify key examples of monuments and symbols associated with caste and explore their cultural, social and political implications.

By the end of the lesson,

participants will be able to:

- Track the banning of a book title in 2024 using a timeline created from articles, videos and state laws.

- Examine the motivations behind book burnings and bannings, including the desire to maintain power, suppress dissent and control information.

- Appreciate the power of symbols across cultures and communities.

- Identify key examples of monuments and symbols associated with caste and explore their cultural, social and political implications.

HOW WE IDENTIFY

When you read the word ‘symbol,’ what comes to mind? For some it could be something personal, such as the mascot for your favorite sports team. For others it may be an item fixed in the community, like a statue. A symbol is an important sign, object or image that can show what someone believes in or supports. Scholar and author Kenneth Burke, an expert in symbols and how they shape human behavior, states humans “understand their world by depicting it in symbols, and by placing meaning on events.” Humanity has done so for thousands of years.

In an effort to unite people, “our ancestors began to design telegraphic symbols to represent beliefs and to identify affiliations,” and connect like-minded people. Symbols are oftentimes used to represent ideologies, but does a drawing, flag or colorful design truly have the power to unite people? Can they be used in a heinous way to perpetuate oppressive beliefs and keep caste systems in place?

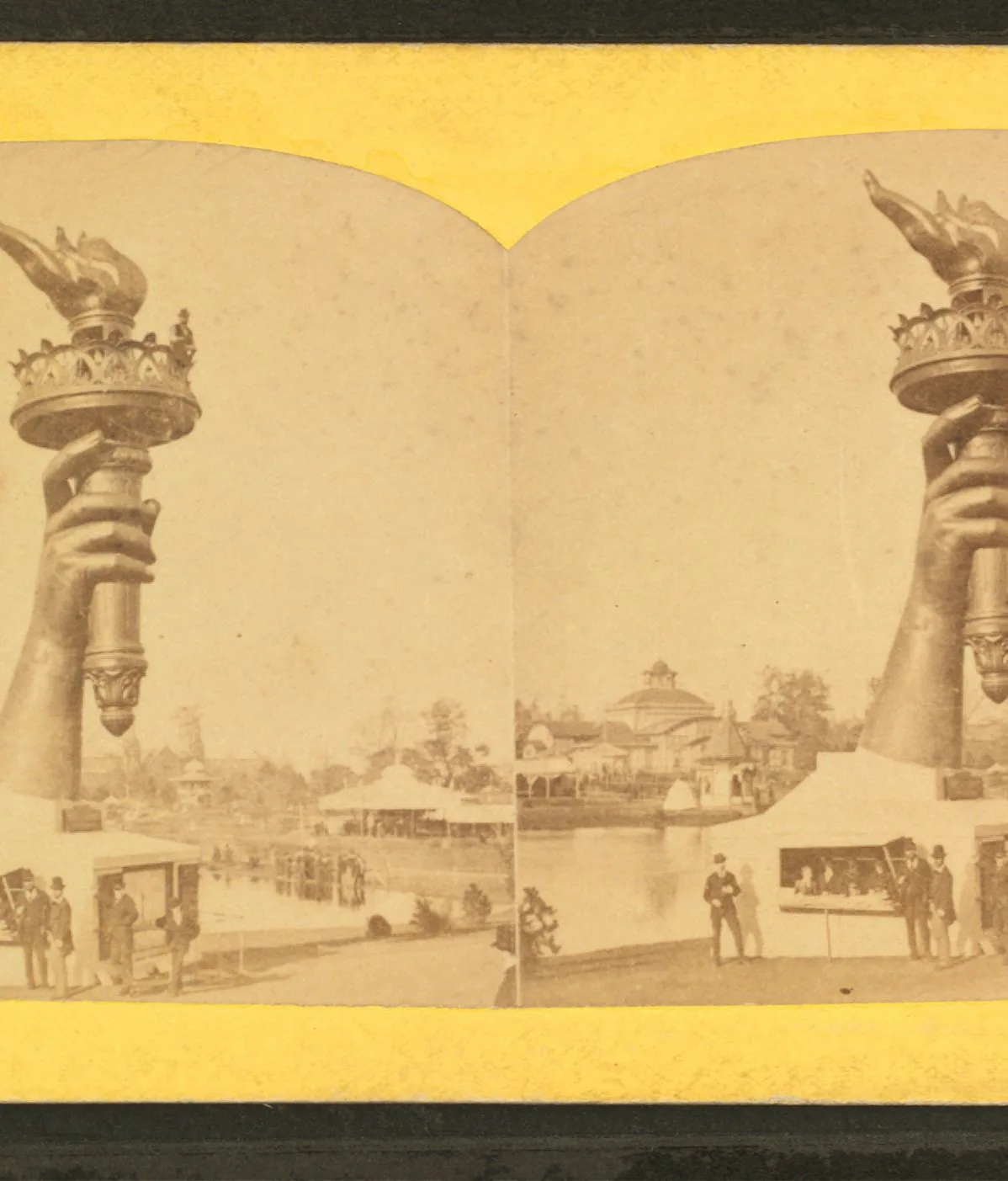

Take a look at these two statues from 1876.

Image Credit: Bettman, Getty Black History and Culture

The Statue of the Freed Slave stood in Memorial Hall during the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The event coincided with the 100th anniversary of the adoption of America’s Declaration of Independence.

Also at the same exposition was Frederic Auguste Bartholdi’s Colossal Hand and Torch, a portion of what would later become the United States’ Statue of Liberty, displayed in an effort to raise money and garner attention for the completion of the project. Visitors were able to get up close and personal by climbing a ladder up to the statue’s torch.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

- How do the “Statue of the Freed Slave” and the “Colossal Hand and Torch” symbolize different (or the same) ideas or beliefs?

- What historical events or contexts are associated with each symbol?

- In what ways do these symbols represent freedom or liberation?

- What messages or values might each symbol convey to people who see them?

- Are there any similarities in the design or presentation of these symbols?

- How do you think people from different backgrounds or perspectives might interpret these symbols differently?

- Do you think symbols have the power to shape attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors in society? If so, how?

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

- How do the “Statue of the Freed Slave” and the “Colossal Hand and Torch” symbolize different (or the same) ideas or beliefs?

- What historical events or contexts are associated with each symbol?

- In what ways do these symbols represent freedom or liberation?

- What messages or values might each symbol convey to people who see them?

- Are there any similarities in the design or presentation of these symbols?

- How do you think people from different backgrounds or perspectives might interpret these symbols differently?

- Do you think symbols have the power to shape attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors in society? If so, how?

WHO DECIDES WHAT KNOWLEDGE MATTERS?

The Philadelphia Exposition was held during the Reconstruction Era in the United States, and gave space for the celebration of achievements by many people, including women, Indigenous Americans and Black Americans. The organizers made a choice to be inclusive (as much as can be expected for the time period) and visitors were able to tour exhibits and come to their own conclusions about the importance of the information they were viewing.

But what if the organizers made a different choice?

Have you ever experienced the frustration of having your opinion silenced or being denied the opportunity to view, listen to or read something that piqued your curiosity? Imagine that very feeling magnified across centuries and civilizations, where the deliberate act of suppressing information has been employed as a form of social hierarchy to control communities.

In 1933, that’s what happened to husband and wife anthropologists Allison Davis and Elizabeth Stubbs Davis while researching and studying in Berlin, Germany. In “ORIGIN,” we meet them as they attempt to check out a library book by acclaimed author Erich Maria Remarque (All Quiet on the Western Front), not knowing it has been banned and burned by the Nazi Party.

Suppression of Knowledge is Nothing New

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

In “ORIGIN,” The Davises find themselves in Germany at a critical moment in history.

Throughout the course of human history, deliberate suppression of literature has been used as a potent instrument to restrict information, construct narratives and maintain social or political control. This practice dates back to ancient times.

The suppression of information, literature and knowledge is on the rise, and, according to the American Library Association, reached a record high in 2022. According to their records, more than 1,200 challenges of library books were issued in the United States in 2022 alone, nearly double the previous record from 2021 and by far the most since the ALA began keeping data 20 years ago. In 2023, the trend continued to escalate, with a 33% increase over the previous school year.

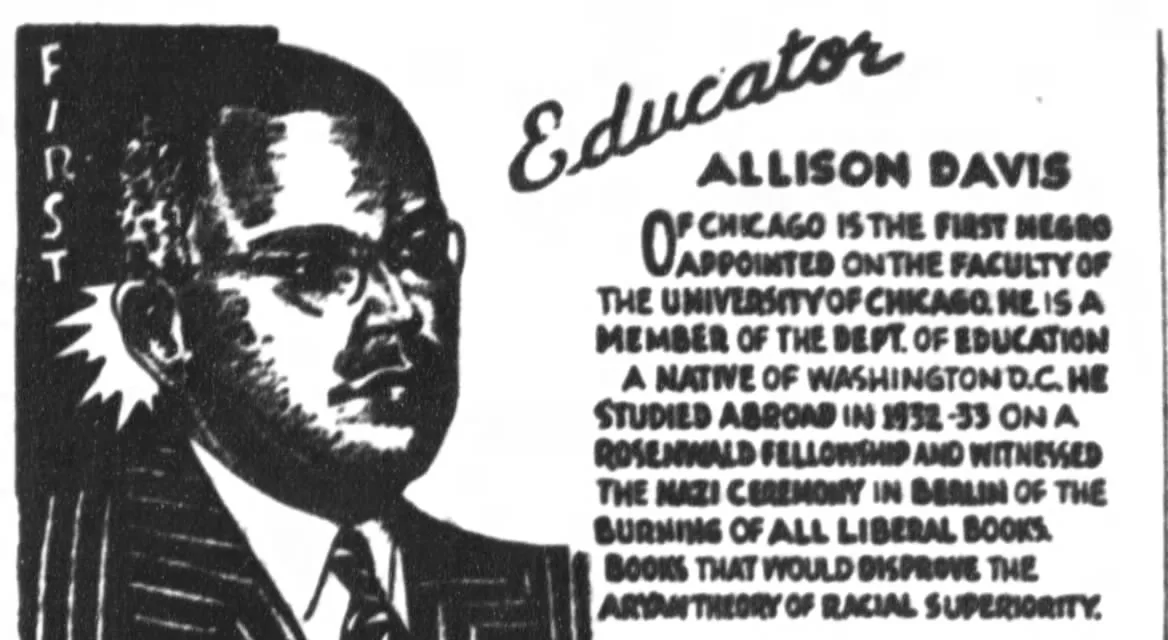

Credits: St. Paul Recorder (Minneapolis, Minnesota) · 22 Nov 1946, Fri · Page 4

Allison Davis’ appointment to the University of Chicago was featured in the African American newspaper the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, in 1946. The clipping highlights the fact that Allison (and wife Elizabeth) witnessed firsthand the burning of books by Nazis in Berlin, Germany.

“On 10 May, 1933, a remarkable act of barbarism, a prelude to the many worse ones that followed, took place in the city of Berlin. Students from the Wilhelm Humboldt University, all of them members of right-wing student organizations, transported books from their university library and from other collections to the Franz Joseph Platz; adjacent to the university. Accompanying their actions with declaimed denunciations of the authors, they proceeded to toss thousands of titles, by writers famous and obscure, foreign and native, into the flames of an already ignited bonfire. The egregiously primitive act lasted for hours, interrupted only by the incantation of Nazi songs and a speech by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.”

– Museum of Tolerance

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

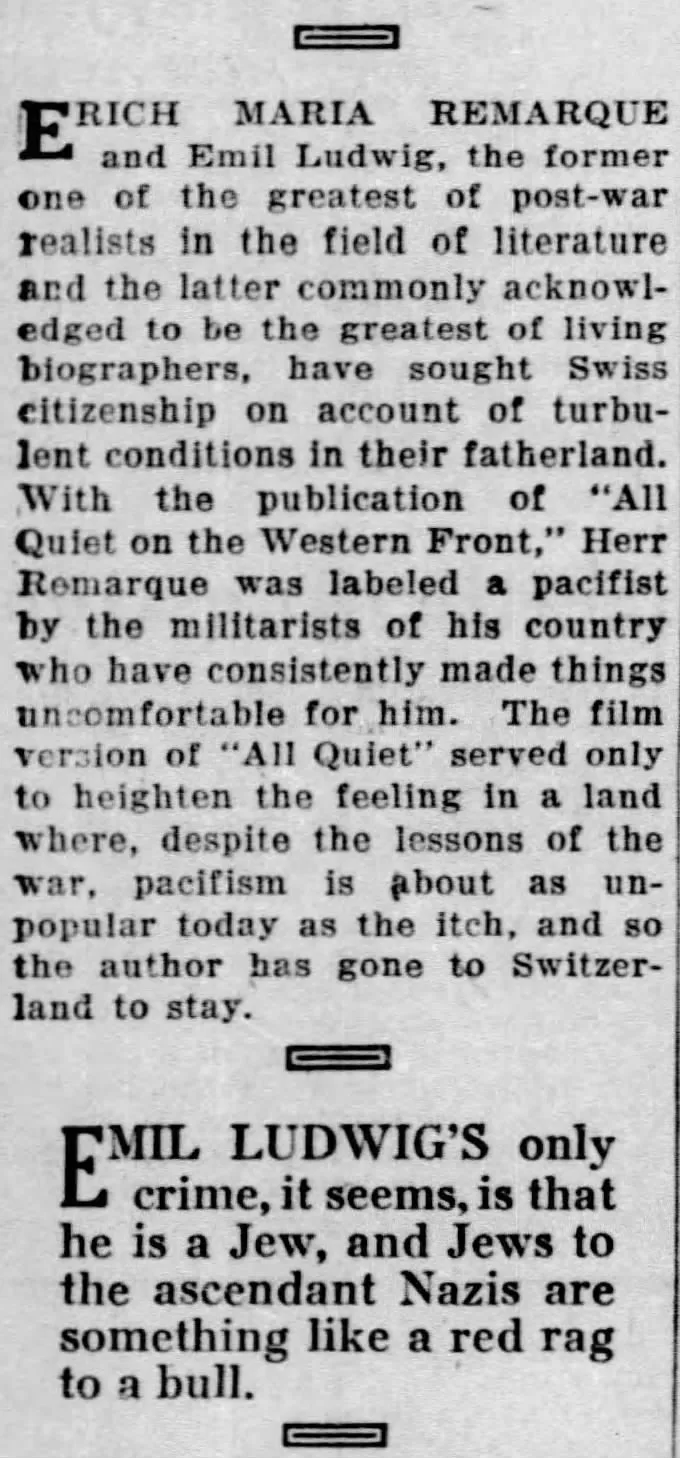

Many of Germany’s most famous works were destroyed that night. Writers such as Erich Maria Remarque, famous for All Quiet on the Western Front, and biographer Emil Ludwig were among the authors targeted by the students because their writing was considered “un-German.”

“The Nazis banned and burned all of Emil Ludwig’s works because of his opposition to Nazi rule, his Jewish heritage, and his sometimes controversial biographies, which they considered “un-German.”

– United State Holocaust Memorial Museum

Suppression of Knowledge is Nothing New

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

In “ORIGIN”, The Davises found themselves in Germany at a critical moment in history.

Throughout the course of human history, deliberate suppression of literature has been used as a potent instrument to restrict information, construct narratives and maintain social or political control. This practice dates back to ancient times.

The suppression of information, literature and knowledge is on the rise, and, according to the American Library Association, reached a record high in 2022. According to their records, more than 1,200 challenges of library books were issued in the United States in 2022 alone, nearly double the previous record from 2021 and by far the most since the ALA began keeping data 20 years ago. In 2023, the trend continued to escalate, with a 33% increase over the previous school year.

Credits: St. Paul Recorder (Minneapolis, Minnesota) · 22 Nov 1946, Fri · Page 4

Allison Davis’ appointment to the University of Chicago was featured in the African American newspaper the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, in 1946. The clipping highlights the fact that Allison (and wife Elizabeth) witnessed firsthand the burning of books by Nazis in Berlin, Germany.

“On 10 May, 1933, a remarkable act of barbarism, a prelude to the many worse ones that followed, took place in the city of Berlin. Students from the Wilhelm Humboldt University, all of them members of right-wing student organizations, transported books from their university library and from other collections to the Franz Joseph Platz; adjacent to the university. Accompanying their actions with declaimed denunciations of the authors, they proceeded to toss thousands of titles, by writers famous and obscure, foreign and native, into the flames of an already ignited bonfire. The egregiously primitive act lasted for hours, interrupted only by the incantation of Nazi songs and a speech by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.”

– Museum of Tolerance

Many of Germany’s most famous works were destroyed that night. Writers such as Erich Maria Remarque, famous for All Quiet on the Western Front, and biographer Emil Ludwig were among the authors targeted by the students because their writing was considered “un-German.”

The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) · 9 Aug 1932, Tue · Page 13

“The Nazis banned and burned all of Emil Ludwig’s works because of his opposition to Nazi rule, his Jewish heritage, and his sometimes controversial biographies, which they considered “un-German.”

– United State Holocaust Memorial Museum

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

The Caste Divide

Allison and Elizabeth would soon leave Berlin, their experiences in Germany laying the groundwork for their 1941 landmark study, “Deep South, A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class,” with co-authors Burleigh B. Gardner and Mary R. Gardner. The book was based on fieldwork in Natchez, Mississippi and its surrounding plantation areas in the 1930s, where both couples lived undercover, immersing themselves into both the Black and White communities of the Jim Crow South over two years. This investigation was the first of its kind and influenced race relations and civil rights movements for generations.

“Gordon Davis tells the story of his parents, Allison Davis and Elizabeth Stubbs Davis, and how they came to research and write ‘Deep South,’ a seminal anthropological study of racism in the American south in the 1930s.” Source: New York Public Library

“Gordon Davis tells the story of his parents, Allison Davis and Elizabeth Stubbs Davis, and how they came to research and write ‘Deep South,’ a seminal anthropological study of racism in the American south in the 1930s.” Source: New York Public Library