Caste is a system that organizes people into a rigid hierarchy based on their perceived social status. Historical markers in your community can play an unseen role in perpetuating this system by glorifying and memorializing figures who uphold caste-based ideals. This idea of caste has affected many parts of communities, including how we remember the past. When you look more closely at historical markers, which are put up to remember important events, people, or places, you can see a strong link between these public memorials and the caste system explored in the film “ORIGIN.”

Caste is a system that organizes people into a rigid hierarchy based on their perceived social status. Historical markers in your community can play an unseen role in perpetuating this system by glorifying and memorializing figures who uphold caste-based ideals. This idea of caste has affected many parts of communities, including how we remember the past. When you look more closely at historical markers, which are put up to remember important events, people, or places, you can see a strong link between these public memorials and the caste system explored in the film “ORIGIN.”

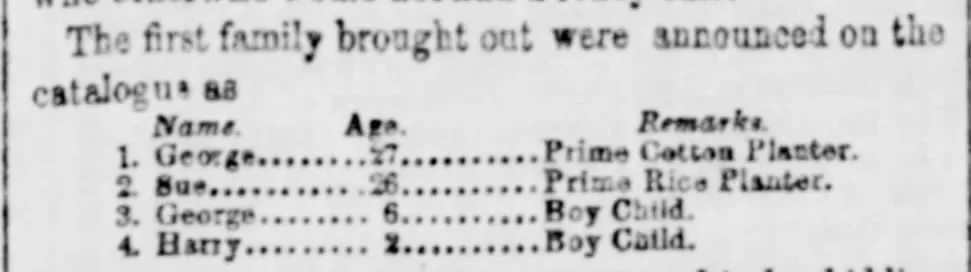

Torrential rain greeted a crowd at Savannah, Georgia’s Ten Broeck Race Course on March 1, 1859. Those invited arrived with money in hand, anxious and willing to weather a literal storm in order to purchase one or more of the 436 men, women and children, including 30 babies, offered for sale. Known today as “the weeping time,” this cruel example of human trafficking that took place over two days would become the largest slave auction in the history of the United States.

Nearly 150 years later, the city of Savannah and state of Georgia have (finally) publicly acknowledged the sale, commemorating it with a historical marker that reads in part, “To satisfy his creditors, Pierce M. Butler sold 436 men, women, and children from his Butler Island and Hampton plantations near Darien, Georgia.”

It took generations of lobbying, petitioning and negotiating before recognition was granted to the enslaved victims of the weeping time. On the nearby Butler Island rice plantation, where the enslaved had been forced to work and live, the state of Georgia erected a historical marker in 1957. However, this marker omits any mention of the 1,000 souls who were enslaved under horrendous conditions on the land, nor does it acknowledge the contributions they made to making the plantation one of the most profitable in the state. That marker simply reads, “Famous rice plantation of the 19th century, owned by Pierce Butler of Philadelphia. A system of dikes and canals for the cultivation of rice, installed by engineers from Holland, is still in evidence in the old fields and has been used as a pattern for similar operations in recent years. During a visit here with her husband in 1839-40, Pierce Butler’s wife, the brilliant English actress Fannie Kemble, wrote her ‘Journal of a Residence On A Georgia Plantation,’ which is said to have influenced England against the Confederacy.”

Photographed By David Seibert, January 20, 2009

While additional markers have been erected over the last decade to honor the enslaved and a robust movement for a larger commemoration continues in the city, the stark contrast between the original marker and the subsequent markers are clear examples of how caste intersects with the teaching of historical facts.

For generations, only one story was told, and it was told through the lens of those in power. It’s time to retell the story of your community in a way that amplifies and celebrates EVERYONE who contributed to building it.

PAUSE AND REFLECT

In a city known for its dedication to protecting and celebrating historical spaces, it took more than 150 years to erect a monument to the largest slave sale in the history of the United States. What reasons may have caused the delay?

ACTIVITY

SET THE RECORD STRAIGHT: ANNOTATION AS ACTIVISM

Let’s annotate! You see a sign in your neighborhood, perhaps by the side of the road or on the wall of a building, that marks a historical location, but you know the information on the marker doesn’t tell the whole story. What do you do next? How can you update a historical marker? Who decides which people, places and events are celebrated (hint: you do).

In this activity, participants will visit (in person) or find (online) historical markers in their communities, create notes expanding upon the information in the marker and add their voices to the historical dialogue happening all around them.

- What two events does the video highlight in the city of Dallas, Texas?

- How are the events connected?

- Why is the marker important?

- What two events does the video highlight in the city of Dallas, Texas?

- How are the events connected?

- Why is the marker important?

Annotation as Activism

Annotation is the grammatical art of modifying text to gain a better understanding. Let’s say you are reading a book about gardening. You might make notes in the margins such as “would work well in the backyard” or “only plant in April.” Your notes contain additional information that gives context to what you are reading. The annotations could go as far as to question or correct something the author has written.

Download this activity and use it to practice your annotation skills and contribute to your community’s history by updating historical markers.

Take a look at this example of annotation from the National Writing Project, where participants were asked to read an article and leave annotations in the margin.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What did you learn through the process of making your annotation?

- Does updating or revisiting sensitive historic information harm communities more than it helps?

- How should the erection of monuments and remembrances in your neighborhood be decided?

- There are costs associated with creating public monuments; who should be responsible for paying for the plaque? How did you come to your conclusion?