- Jacqueline Woodson, American Writer

Caste systems are set and rigid, but human beings are mobile and adaptable. A person’s position within a society can be influenced by their location, the era they live in and the history of their community.

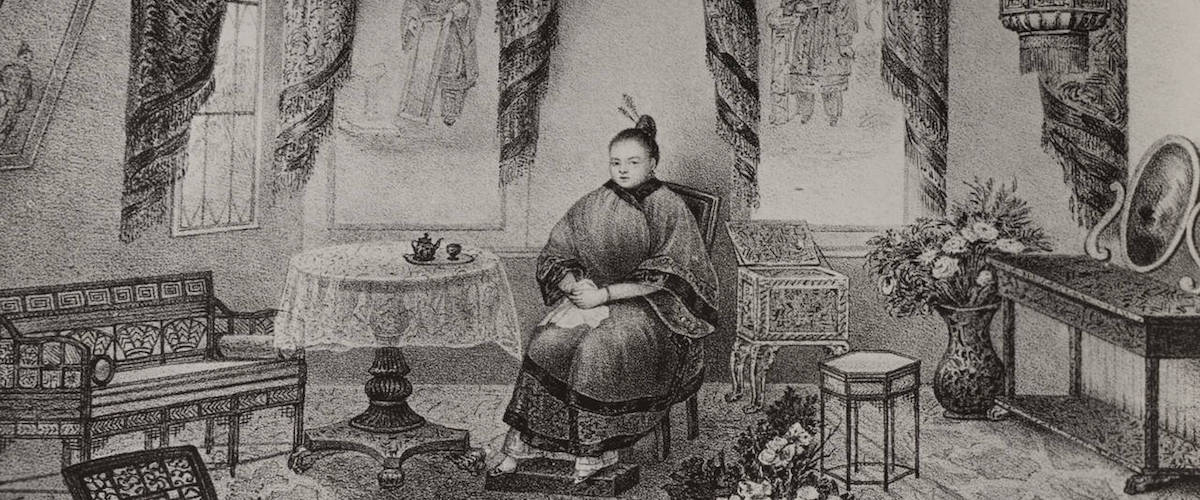

Meet Miss Afong Moy of New York

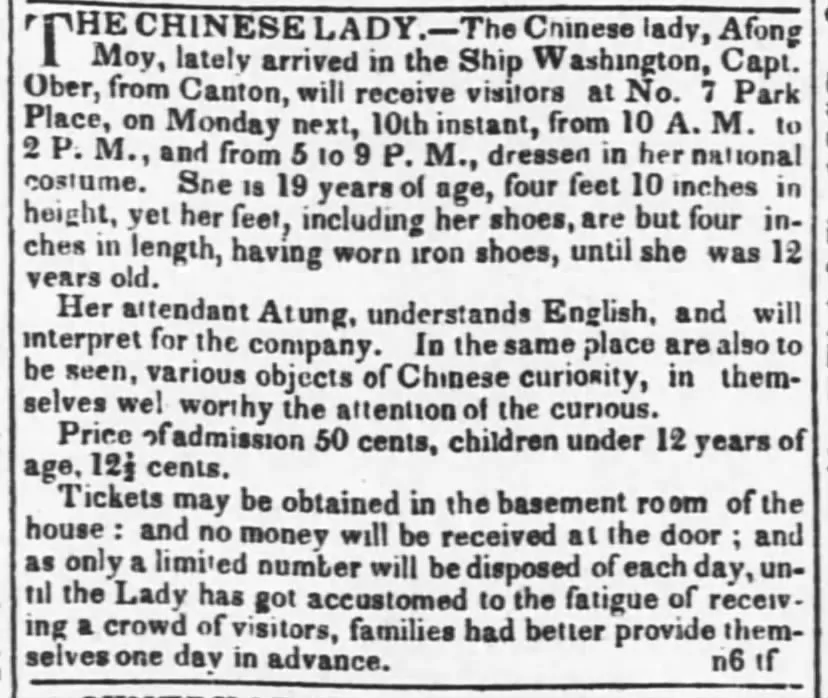

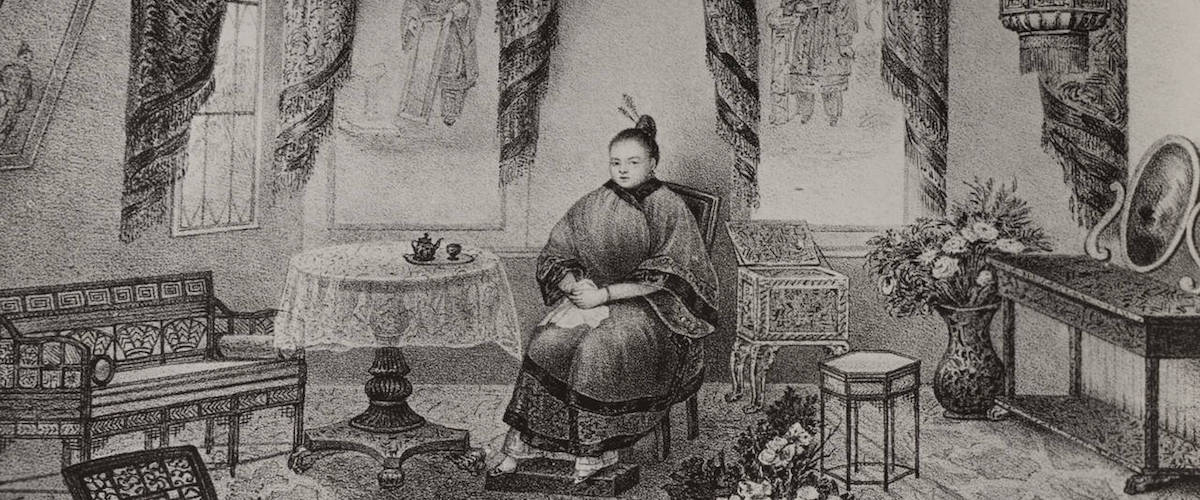

In 1834, New York's elite class buzzed with excitement over the arrival of Miss Afong Moy. Often referred to in news accounts from the time as the “Chinese Lady," she is known as the first Chinese woman to visit the United States. Her presence captivated society; newspapers spotlighted her ornate attire and delicate feet, while reporters and visitors praised her "quiet demeanor" and "imperturbable composure."

The intrigue surrounding Moy, a person from a distant land with a different ethnic background, was a stark contrast to an incident that happened that same year - the Farren Riots. These riots were a violent outburst of racism against Black citizens in New York City, showing the darker side of societal hierarchy.

Credits: The Evening Post (New York, New York) · 8 Nov 1834, Sat · Page 3

Acceptance and Alienation

What can we learn from these events? For starters, they highlight how acceptance in a society can be both unpredictable and discriminatory. Even though we define caste positions as fixed, who society values can change depending on the time, place and broader movements happening in society. An individual might belong to one social class in a certain city or country and find themselves in another social class the moment they move or emigrate. A group of people could be of the highest class in one generation and then, hundreds of years later, be the lowest class.

Following Ms. Afong Moy's visit, the mid-nineteenth century saw a large influx of Chinese immigrants to America, largely caused by the California Gold Rush of 1849. Like Moy, these immigrants were welcomed and immediately put to work. By the early 1880s, however, the growing Chinese population in the United States began facing increased racial and ethnic discrimination, mirroring the experiences of their Black counterparts.

This discrimination was codified into American law with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which restricted Chinese immigration and reinforced a social order based on race.

Take a look at the video below:

The Binary Construction of Race

It’s important to realize that belonging and othering are complex and interconnected concepts. In the film "ORIGIN", we learn that while caste systems may lay the groundwork for societal hierarchies, race can act as the yardstick determining one's place within these hierarchies.

Because so many communities allow race to hold significant social and cultural weight, it's important to remember that race lacks a scientific basis.

When it comes to the binary construction of Blackness and whiteness, it's important to remember that these definitions are quintessential American inventions and became the way we categorize people when the United States was still transitioning from a colony to a country. Colonists constructed identities of "Blackness" and "whiteness" to suit their interests as they were forming a new nation. The new identities aided the colonists, who were forcefully trafficking and shipping Africans into many countries, including the present-day United States.

During early waves of migration to the Americas, in the 1600s, European colonists chose names for themselves based on their countries of origin. They referred to themselves as British, Irish, Scottish, Dutch, French and more. From the late 1600s to the 1800s, colonists began to construct a national identity to establish themselves as one homogeneous group. As Europeans in the North American colonies, they sought ways to come together as a new nation. Their efforts to create a national identity resulted in a binary construction of race: "Black" as one side of the binary and "white" as the other side.

Over time, enslaved Africans in America became "Black" and Europeans became "white." Blackness was falsely crafted—through scientific racism—to align with low intellectual capacity, high physical endurance for labor and criminal behavior. Whiteness, on the other hand, was socially constructed to represent positive characteristics synonymous in many communities with goodness, righteousness, purity and morality.

This construction was the process of nation-building, and the American colonists shaped the type of nation they were building with great intentionality. In order to build one nation — a "United States" — the "founding fathers" had to unite the various groups of European colonists under one national identity. That identity was a socially constructed "white" identity.

Organizations such as the American Psychological Association (APA), which has been around since the late 1800s, helped to construct such ideas. Recently in their apology to people of color for their role in perpetuating racism, the APA said that "race is a social construct with no underlying genetic or biological basis," and it debunked the idea "that different groups can be ranked hierarchically on the basis of physical characteristics."

Video Credit: VOX

VIDEO: You may know exactly what race you are, but how would you prove it if somebody disagreed with you? Jenée Desmond Harris explains.

Eugenics and Scientific Racism

In 2007, Dr. James Watson, who shared a 1962 Nobel Prize for co-discovering the structure of DNA, told a British journalist that he was "inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa" because "all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours, whereas all the testing says, not really." In other words, Watson believed Black people were unintelligent genetically, even if social policies did not affirm this.

Although the mainstream scientific community ostracized Watson for his claims and cut funding for his research, white supremacists used his ideas to perpetuate their arguments of racial superiority.

Watson's scientifically racist ideas do not exist in isolation. He represents an entire pseudo-science called eugenics. Eugenics argues that society can improve the human species by selectively mating people together who have specific desirable hereditary traits. Eugenicists argue that this practice could reduce human suffering by "breeding out" disease, disability and so-called undesirable characteristics from the human population.

Hitler Did What?

It is widely known that Adolf Hitler's genocidal plan for Jewish families in Nazi Germany was predicated on eugenics. But Hitler's ideas were also specifically informed by American eugenics. Hitler himself made frequent mention of having used the American "Trail of Tears" and native expulsion, as well as the American Jim Crow South, as models for Nazi concentration camps and the systematic genocide of Jewish people.

How America Uses Race

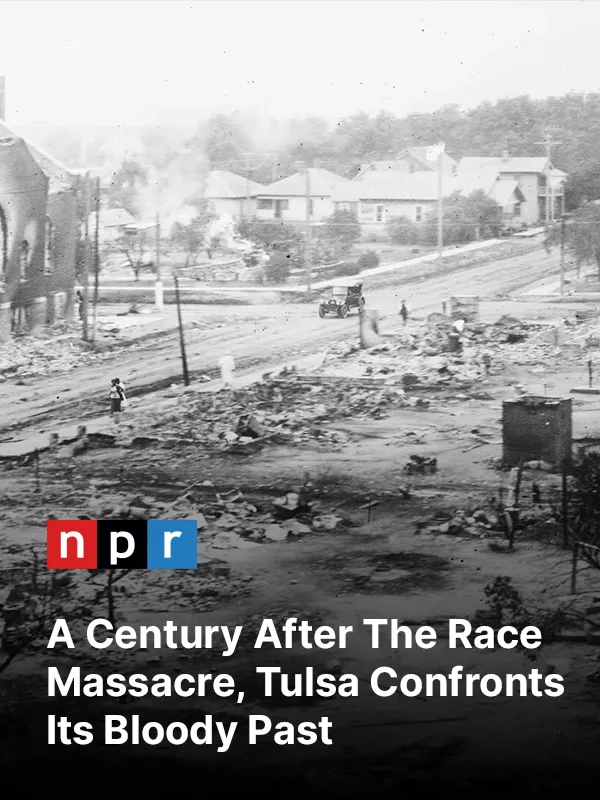

A little more than ten years before Hitler’s rise to power, in a small but prosperous American town known as Tulsa, Oklahoma, Black Americans experienced the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. This violent and racially motivated incident still stands as one of the worst incidents of racial violence in United States history. The event was a reminder in the Jim Crow South of who and what belonged.

On May 31, 1921, a young Black man, Dick Rowland, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white elevator operator. Rumors of the incident spread and a mob of white residents gathered outside the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be handed over to them for lynching. The situation quickly escalated into widespread violence. During the night of May 31 and into the following day, white mobs, some of whom were deputized by local authorities, attacked and destroyed homes, businesses and churches in the Greenwood District. The area was looted, set on fire and subjected to aerial bombardment. The Black residents of Greenwood, who outnumbered their white attackers, organized themselves in self-defense, but they were ultimately overwhelmed by the better-armed white mob. Martial law was declared, and the National Guard was called in to restore order.

The exact number of fatalities is still uncertain, but estimates range from 100 to 300 people, primarily Black people. Many were injured, and thousands were left homeless as their properties were destroyed. The incident resulted in the displacement and impoverishment of the Greenwood community. The immediate aftermath of the massacre involved a systematic cover-up. Reports and documentation of the event were deliberately destroyed or suppressed. Eyewitness accounts were often disregarded or dismissed. The local government and law enforcement authorities downplayed and minimized the violence, aiming to protect the city's reputation and avoid accountability.

Members of the community are now asking for reparations to restore their losses.

Meet Miss Afong Moy of New York

In 1834, New York's elite class buzzed with excitement over the arrival of Miss Afong Moy. Often referred to in news accounts from the time as the “Chinese Lady," she is known as the first Chinese woman to visit the United States. Her presence captivated society; newspapers spotlighted her ornate attire and delicate feet, while reporters and visitors praised her "quiet demeanor" and "imperturbable composure."

The intrigue surrounding Moy, a person from a distant land with a different ethnic background, was a stark contrast to an incident that happened that same year - the Farren Riots. These riots were a violent outburst of racism against Black citizens in New York City, showing the darker side of societal hierarchy.

Credits: The Evening Post (New York, New York) · 8 Nov 1834, Sat · Page 3

Acceptance and Alienation

What can we learn from these events? For starters, they highlight how acceptance in a society can be both unpredictable and discriminatory. Even though we define caste positions as fixed, who society values can change depending on the time, place and broader movements happening in society. An individual might belong to one social class in a certain city or country and find themselves in another social class the moment they move or emigrate. A group of people could be of the highest class in one generation and then, hundreds of years later, be the lowest class.

Following Ms. Afong Moy's visit, the mid-nineteenth century saw a large influx of Chinese immigrants to America, largely caused by the California Gold Rush of 1849. Like Moy, these immigrants were welcomed and immediately put to work. By the early 1880s, however, the growing Chinese population in the United States began facing increased racial and ethnic discrimination, mirroring the experiences of their Black counterparts.

This discrimination was codified into American law with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which restricted Chinese immigration and reinforced a social order based on race.

Take a look at the video below:

The Binary Construction of Race

It’s important to realize that belonging and othering are complex and interconnected concepts. In the film "ORIGIN", we learn that while caste systems may lay the groundwork for societal hierarchies, race can act as the yardstick determining one's place within these hierarchies.

Because so many communities allow race to hold significant social and cultural weight, it's important to remember that race lacks a scientific basis.

When it comes to the binary construction of Blackness and whiteness, it's important to remember that these definitions are quintessential American inventions and became the way we categorize people when the United States was still transitioning from a colony to a country. Colonists constructed identities of "Blackness" and "whiteness" to suit their interests as they were forming a new nation. The new identities aided the colonists, who were forcefully trafficking and shipping Africans into many countries, including the present-day United States.

During early waves of migration to the Americas, in the 1600s, European colonists chose names for themselves based on their countries of origin. They referred to themselves as British, Irish, Scottish, Dutch, French and more. From the late 1600s to the 1800s, colonists began to construct a national identity to establish themselves as one homogeneous group. As Europeans in the North American colonies, they sought ways to come together as a new nation. Their efforts to create a national identity resulted in a binary construction of race: "Black" as one side of the binary and "white" as the other side.

Over time, enslaved Africans in America became "Black" and Europeans became "white." Blackness was falsely crafted—through scientific racism—to align with low intellectual capacity, high physical endurance for labor and criminal behavior. Whiteness, on the other hand, was socially constructed to represent positive characteristics synonymous in many communities with goodness, righteousness, purity and morality.

This construction was the process of nation-building, and the American colonists shaped the type of nation they were building with great intentionality. In order to build one nation — a "United States" — the "founding fathers" had to unite the various groups of European colonists under one national identity. That identity was a socially constructed "white" identity.

Organizations such as the American Psychological Association (APA), which has been around since the late 1800s, helped to construct such ideas. Recently in their apology to people of color for their role in perpetuating racism, the APA said that "race is a social construct with no underlying genetic or biological basis," and it debunked the idea "that different groups can be ranked hierarchically on the basis of physical characteristics."

Video Credit: VOX

VIDEO: You may know exactly what race you are, but how would you prove it if somebody disagreed with you? Jenée Desmond Harris explains.

Eugenics and Scientific Racism

In 2007, Dr. James Watson, who shared a 1962 Nobel Prize for co-discovering the structure of DNA, told a British journalist that he was "inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa" because "all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours, whereas all the testing says, not really." In other words, Watson believed Black people were unintelligent genetically, even if social policies did not affirm this.

Although the mainstream scientific community ostracized Watson for his claims and cut funding for his research, white supremacists used his ideas to perpetuate their arguments of racial superiority.

Watson's scientifically racist ideas do not exist in isolation. He represents an entire pseudo-science called eugenics. Eugenics argues that society can improve the human species by selectively mating people together who have specific desirable hereditary traits. Eugenicists argue that this practice could reduce human suffering by "breeding out" disease, disability and so-called undesirable characteristics from the human population.

Hitler Did What?

It is widely known that Adolf Hitler's genocidal plan for Jewish families in Nazi Germany was predicated on eugenics. But Hitler's ideas were also specifically informed by American eugenics. Hitler himself made frequent mention of having used the American "Trail of Tears" and native expulsion, as well as the American Jim Crow South, as models for Nazi concentration camps and the systematic genocide of Jewish people.

How America Uses Race

A little more than ten years before Hitler’s rise to power, in a small but prosperous American town known as Tulsa, Oklahoma, Black Americans experienced the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. This violent and racially motivated incident still stands as one of the worst incidents of racial violence in United States history. The event was a reminder in the Jim Crow South of who and what belonged.

On May 31, 1921, a young Black man, Dick Rowland, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white elevator operator. Rumors of the incident spread and a mob of white residents gathered outside the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be handed over to them for lynching. The situation quickly escalated into widespread violence. During the night of May 31 and into the following day, white mobs, some of whom were deputized by local authorities, attacked and destroyed homes, businesses and churches in the Greenwood District. The area was looted, set on fire and subjected to aerial bombardment. The Black residents of Greenwood, who outnumbered their white attackers, organized themselves in self-defense, but they were ultimately overwhelmed by the better-armed white mob. Martial law was declared, and the National Guard was called in to restore order.

The exact number of fatalities is still uncertain, but estimates range from 100 to 300 people, primarily Black people. Many were injured, and thousands were left homeless as their properties were destroyed. The incident resulted in the displacement and impoverishment of the Greenwood community. The immediate aftermath of the massacre involved a systematic cover-up. Reports and documentation of the event were deliberately destroyed or suppressed. Eyewitness accounts were often disregarded or dismissed. The local government and law enforcement authorities downplayed and minimized the violence, aiming to protect the city's reputation and avoid accountability.

Members of the community are now asking for reparations to restore their losses.

WHAT IS THE CENSUS?

The History of Everything, PBS

Questioning Who You Are

The changing perceptions, meanings and classifications of race in the United States census have changed dramatically over time. Every census taken in America since 1790 has included questions about race and ethnicity, although the racial categories used have evolved in response to shifting political and scientific understandings. Immigration, enslavement and labor practices have all contributed to how people are allowed to be categorized and who can choose to call themselves by certain racial designations.

Sociologist Aliya Saperstein from the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality found that a person’s racial designation can change based on factors such as unemployment and imprisonment. Using data collected from interviews with the same group of people over many years, the data showed that people labeled as one race early in the study could have that race changed by the survey taker if they admitted to having lost a job or having been arrested. “What our research challenges,” says Saperstein, “Is this idea that the race of an individual is fixed. 20 percent of the respondents…experienced at least one change in how the interviewer perceived them by race over the course of different observations.”

WATCH an interview with Dr. Saperstein and answer the reflection questions that follow:

WHAT IS THE CENSUS?

The History of Everything, PBS

QUESTIONS, QUESTIONS, QUESTIONS

The changing perceptions, meanings and classifications of race in the United States census have changed dramatically over time. Every census taken in America since 1790 has included questions about race and ethnicity, although the racial categories used have evolved in response to shifting political and scientific understandings. Immigration, enslavement and labor practices have all contributed to how people are allowed to be categorized and who can choose to call themselves by certain racial designations.

Sociologist Aliya Saperstein from the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality found that a person’s racial designation can change based on factors such as unemployment and imprisonment. Using data collected from interviews with the same group of people over many years, the data showed that people labeled as one race early in the study could have that race changed by the survey taker if they admitted to having lost a job or having been arrested. “What our research challenges,” says Saperstein, “Is this idea that the race of an individual is fixed. 20 percent of the respondents…experienced at least one change in how the interviewer perceived them by race over the course of different observations.”

WATCH an interview with Dr. Saperstein and answer the reflection questions that follow:

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Given that humans are more alike than they are different, explore whether there’s really a scientific reason to divide people into races.

- The U.S. Census plays a crucial role in determining the allocation of federal funds to communities. By collecting detailed demographic information, the Census helps ensure that resources are distributed based on the needs and population sizes of different areas, impacting everything from healthcare and education to infrastructure and social services. If racial designations no longer existed on the United States Census, how might that impact communities?

- Consider the impact of changeable racial identities on promoting diversity and inclusion. How might the ability to shift racial categorizations enhance or complicate efforts to achieve a more inclusive society?

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Given that humans are more alike than they are different, explore whether there’s really a scientific reason to divide people into races.

- The U.S. Census plays a crucial role in determining the allocation of federal funds to communities. By collecting detailed demographic information, the Census helps ensure that resources are distributed based on the needs and population sizes of different areas, impacting everything from healthcare and education to infrastructure and social services. If racial designations no longer existed on the United States Census, how might that impact communities?

- Consider the impact of changeable racial identities on promoting diversity and inclusion. How might the ability to shift racial categorizations enhance or complicate efforts to achieve a more inclusive society?

ACTIVITY

Evolution of Identity: How the Census Categorizes Us

Census

Census

Free Whites and Enslaved Blacks

The 1790 census created a clear distinction between "free white" and Black enslaved people. The census questions asked for the name of the head of the family and the number of people in each household, and specified race in its questions. Specifically, census takers were interested in the number of free white males 16 years of age and older, free white males under age 16, free white families, all other free persons, and the number of enslaved people held by the head of household. Nearly 700,000 enslaved men, women and children were counted in this census, representing just under 18% of the population of the 13 states and southwest territory.

Census

Census

Mulatto: Blacks with White Heritage

At the request of a racial scientist named Josiah Nott, the term "mulatto" was first used in the 1850 census to describe people of Black and white heritage. Nott included "mulatto" as part of a study he was conducting to see if there was any kind of drop-off in one's lifespan due to a "Black" heritage. The 1860 census continued this trend of expanding racial categories by including separate designations for "Black," "mulatto" and "white" people, and by noting the rise in the number of freed slaves.

Census

Census

Chinese, Indians and Negroes

As numerous immigrants came from China to work on the Central Pacific Railroad, the term "Chinese" was officially adopted as the first racial group for Asians in the United States in 1870. The 1870 census was the first to use the term "color or race," and it included new categories for people of other races, such as "Chinese," "Indian" and "Negro." These new subgroups were created because of the growing diversity of the United States as a result of immigration and small steps in the acceptance of people of color. The 1870 census was also the first time that all formerly enslaved people could be listed by name. Previously they were listed by gender and age on the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules, and only the name of the enslaver was written in the document.

Census

Census

The Quadroons and Octoroons

In 1890, two new categories were introduced: "quadroon" and "octoroon," which, respectively, denoted one-fourth and one-eighth African ancestry. Although these classifications only lasted for one census cycle, they indicate that white legislators, interested in the concept of purity, and, in particular, the purity of whites, as opposed to Blacks.

Census

Census

How Italians Become White during Columbus Day

The federal holiday honoring the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus was integral to the process by which Italian Americans were fully ratified as white in the twentieth century. The first celebration of the holiday took place in 1892, when President Harrison attempted to calm the outrage of Italian Americans following a horrific New Orleans lynching of 11 Italian Americans. The holiday's justification, while entrenched in myth, allowed Italian Americans to eventually carve a laudatory portrayal of themselves into the civic record.

Census

Census

Japanese, Filipinos and Hindus

Increased immigration from Asia and the Pacific led to the census of 1900 expanding racial categories to include groupings like "Japanese," "Filipino" and "Hindu."

Census

Census

Census

Census

Individuals are able to choose their own racial background

Not until 1960 did individuals have the option to choose their own racial background. Before that point, racial classifications were made by the enumerators who conducted censuses.

Census

Census

Another Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin

The census form did not include any questions about Hispanic origin as a distinct category from race until 1970. The 1970 census included three pre-populated Hispanic origin categories on the form, and a fourth, "Another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin," where you could provide a more precise origin.

Census

Census

From Hindus to Other Asians and Pacific Islanders

Although the option to identify as "Other" first appeared on census forms in 1910, most people who checked that box were actually Korean, Filipino or Asian Indian. After some time, the Asian racial categories were broadened, and "Other" or "Some other race" was included. From 1920 to 1940, all Asian Indians were grouped together and incorrectly labeled as "Hindus" on the census form. Starting in the year 2000, respondents were given the option of selecting from seven distinct Asian groupings, including "Other Asian," as well as writing in their own response.

Censuses conducted between 1960 and 1990 expanded the definition of "Asian" to include people of Hawaiian, Part Hawaiian, Samoan and Guamanian ancestry. Based on studies by the Census Bureau and revised OMB standards, Native Hawaiians, Samoans and Guamanians were grouped together as Pacific Islanders starting in the year 2000.

Census

Census

Additional information on ethnicities after selecting "white" or "Black"

For the first time, in 2020, the form specifically requested additional information from respondents who selected "white" or "Black" as their race. This could include the respondent's country of origin, such as Germany, Lebanon, Africa or Somalia.

As late as the 2020 census, the definition of "Asian" remained contested. 42% of white Americans, according to a 2016 National Asian American Survey study, believe that Indians are "not likely to be" Asian or Asian American, while 45% believe that Pakistanis are "not likely to be" Asian or Asian American. In addition, 27% of Asian Americans believed that Pakistanis are "not likely to be" Asian or Asian Americans, while 15% of Asian Americans believed the same of Indians. The researchers concluded that the question of Asian American identity is contested, with South Asian groups (Indians and Pakistanis) finding it more difficult for American society to view them as Asian Americans.

Census

Census

HISPANIC OR LATINO AS ONE RACE/ETHNICITY CATEGORY AND A NEW CHECKBOX FOR PEOPLE OF MIDDLE EASTERN OR NORTH AFRICAN DESCENT

The survey question about race or ethnicity has been updated to encompass seven main categories: White, Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Middle Eastern or North African and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

Before, individuals of Hispanic origin were presented with a two-part inquiry regarding their identity: initially asked about their Hispanic or Latino background, followed by selecting a racial category such as White, Black, American Indian or another race. Now, Hispanic or Latino is listed as one of the main categories. Furthermore, the inclusion of a Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) category would enable 7 to 8 million individuals to avoid categorizing themselves as "white" or "other" on census and other data collection forms.

Free Whites and Enslaved Blacks

The 1790 census created a clear distinction between "free white" and Black enslaved people. The census questions asked for the name of the head of the family and the number of people in each household, and specified race in its questions. Specifically, census takers were interested in the number of free white males 16 years of age and older, free white males under age 16, free white families, all other free persons, and the number of enslaved people held by the head of household. Nearly 700,000 enslaved men, women and children were counted in this census, representing just under 18% of the population of the 13 states and southwest territory.

Mulatto: Blacks with White Heritage

At the request of a racial scientist named Josiah Nott, the term "mulatto" was first used in the 1850 census to describe people of Black and white heritage. Nott included "mulatto" as part of a study he was conducting to see if there was any kind of drop-off in one's lifespan due to a "Black" heritage. The 1860 census continued this trend of expanding racial categories by including separate designations for "Black," "mulatto" and "white" people, and by noting the rise in the number of freed slaves.

Chinese, Indians and Negroes

As numerous immigrants came from China to work on the Central Pacific Railroad, the term "Chinese" was officially adopted as the first racial group for Asians in the United States in 1870. The 1870 census was the first to use the term "color or race," and it included new categories for people of other races, such as "Chinese," "Indian" and "Negro." These new subgroups were created because of the growing diversity of the United States as a result of immigration and small steps in the acceptance of people of color. The 1870 census was also the first time that all formerly enslaved people could be listed by name. Previously they were listed by gender and age on the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules, and only the name of the enslaver was written in the document.

The Quadroons and Octoroons

In 1890, two new categories were introduced: "quadroon" and "octoroon," which, respectively, denoted one-fourth and one-eighth African ancestry. Although these classifications only lasted for one census cycle, they indicate that white legislators, interested in the concept of purity, and, in particular, the purity of whites, as opposed to Blacks.

How Italians Become White during Columbus Day

The federal holiday honoring the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus was integral to the process by which Italian Americans were fully ratified as white in the twentieth century. The first celebration of the holiday took place in 1892, when President Harrison attempted to calm the outrage of Italian Americans following a horrific New Orleans lynching of 11 Italian Americans. The holiday's justification, while entrenched in myth, allowed Italian Americans to eventually carve a laudatory portrayal of themselves into the civic record.

Japanese, Filipinos and Hindus

Increased immigration from Asia and the Pacific led to the census of 1900 expanding racial categories to include groupings like "Japanese," "Filipino" and "Hindu."

Individuals are able to choose their own racial background

Not until 1960 did individuals have the option to choose their own racial background. Before that point, racial classifications were made by the enumerators who conducted censuses.

Another Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin

The census form did not include any questions about Hispanic origin as a distinct category from race until 1970. The 1970 census included three pre-populated Hispanic origin categories on the form, and a fourth, "Another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin," where you could provide a more precise origin.

From Hindus to Other Asians and Pacific Islanders

Although the option to identify as "Other" first appeared on census forms in 1910, most people who checked that box were actually Korean, Filipino or Asian Indian. After some time, the Asian racial categories were broadened, and "Other" or "Some other race" was included. From 1920 to 1940, all Asian Indians were grouped together and incorrectly labeled as "Hindus" on the census form. Starting in the year 2000, respondents were given the option of selecting from seven distinct Asian groupings, including "Other Asian," as well as writing in their own response.

Censuses conducted between 1960 and 1990 expanded the definition of "Asian" to include people of Hawaiian, Part Hawaiian, Samoan and Guamanian ancestry. Based on studies by the Census Bureau and revised OMB standards, Native Hawaiians, Samoans and Guamanians were grouped together as Pacific Islanders starting in the year 2000.

Additional information on ethnicities after selecting "white" or "Black"

For the first time, in 2020, the form specifically requested additional information from respondents who selected "white" or "Black" as their race. This could include the respondent's country of origin, such as Germany, Lebanon, Africa or Somalia.

As late as the 2020 census, the definition of "Asian" remained contested. 42% of white Americans, according to a 2016 National Asian American Survey study, believe that Indians are "not likely to be" Asian or Asian American, while 45% believe that Pakistanis are "not likely to be" Asian or Asian American. In addition, 27% of Asian Americans believed that Pakistanis are "not likely to be" Asian or Asian Americans, while 15% of Asian Americans believed the same of Indians. The researchers concluded that the question of Asian American identity is contested, with South Asian groups (Indians and Pakistanis) finding it more difficult for American society to view them as Asian Americans.

HISPANIC OR LATINO AS ONE RACE/ETHNICITY CATEGORY AND A NEW CHECKBOX FOR PEOPLE OF MIDDLE EASTERN OR NORTH AFRICAN DESCENT

The survey question about race or ethnicity has been updated to encompass seven main categories: White, Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Middle Eastern or North African and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

Before, individuals of Hispanic origin were presented with a two-part inquiry regarding their identity: initially asked about their Hispanic or Latino background, followed by selecting a racial category such as White, Black, American Indian or another race. Now, Hispanic or Latino is listed as one of the main categories. Furthermore, the inclusion of a Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) category would enable 7 to 8 million individuals to avoid categorizing themselves as "white" or "other" on census and other data collection forms.

RACIAL CENSUS AS THE IMAGE OF A NATION

Throughout its history, the United States Census has often treated “whiteness” as the default, placing individuals with mixed heritage into the non-white category. The Census itself doesn’t inherently create or sustain racial hierarchies; it is how those in power use the data to formulate policies that reinforce these divisions. Jennifer Hochschild notes, “A modern census helps to construct and reconstruct an ethnoracial order in four ways: by providing the taxonomy and language of race; generating the informational content for that taxonomy: facilitating the development of public policies; and generating numbers upon which claims to political representation are made.” This indicates the census’s role in upholding the dominance of certain groups, establishing boundaries, and legitimizing control over marginalized groups, thus reflecting and shaping national identity.

RACIAL CENSUS AS THE IMAGE OF A NATION

Throughout its history, the United States Census has often treated “whiteness” as the default, placing individuals with mixed heritage into the non-white category. The Census itself doesn’t inherently create or sustain racial hierarchies; it is how those in power use the data to formulate policies that reinforce these divisions. Jennifer Hochschild notes, “A modern census helps to construct and reconstruct an ethnoracial order in four ways: by providing the taxonomy and language of race; generating the informational content for that taxonomy: facilitating the development of public policies; and generating numbers upon which claims to political representation are made.” This indicates the census’s role in upholding the dominance of certain groups, establishing boundaries, and legitimizing control over marginalized groups, thus reflecting and shaping national identity.

HANDS-ON ACTIVATIONS

Here are three ways learners can use this timeline to bring the lesson to life.

- Host a debate with friends, family members or classmates on whether the U.S. census should continue to include racial and ethnic categorizations, and what the implications might be either way.

- Draft a proposal for how you believe racial and ethnic categorizations should be handled in future censuses, backed up with reasons and potential implications.

- Organize a panel discussion with community members from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds to share their perspectives on census categorizations and their societal implications.

HANDS-ON ACTIVATIONS

Here are three ways learners can use this timeline to bring the lesson to life.

- Host a debate with friends, family members or classmates on whether the U.S. census should continue to include racial and ethnic categorizations, and what the implications might be either way.

- Draft a proposal for how you believe racial and ethnic categorizations should be handled in future censuses, backed up with reasons and potential implications.

- Organize a panel discussion with community members from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds to share their perspectives on census categorizations and their societal implications.