- Audre Lorde

Race on Trial

In the next activity, look at key court decisions about race in American law and see how each case either upheld or challenged racial-based social structures.

“America has a long-standing history of racism and segregation, and courts provide well-documented examples of it.” — Rona Alondra, Esquire Magazine

Landmark Cases Around Race

Click on a year on the timeline to explore a court case centered around race in America.

Landmark Cases

Around Race

Click on a year on the timeline to explore a court case centered around race in America.

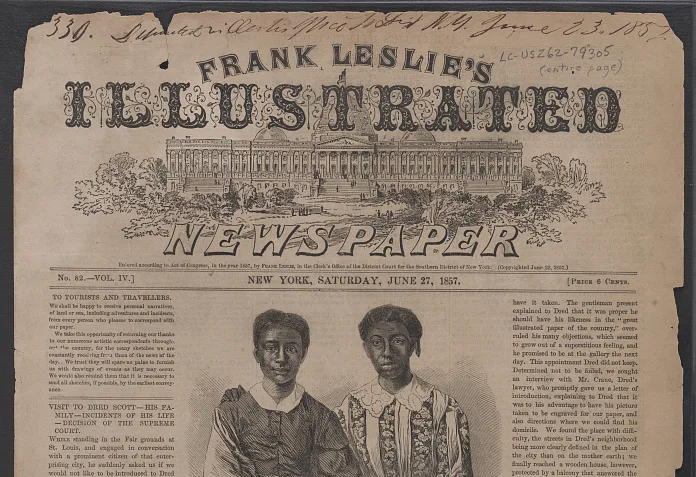

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

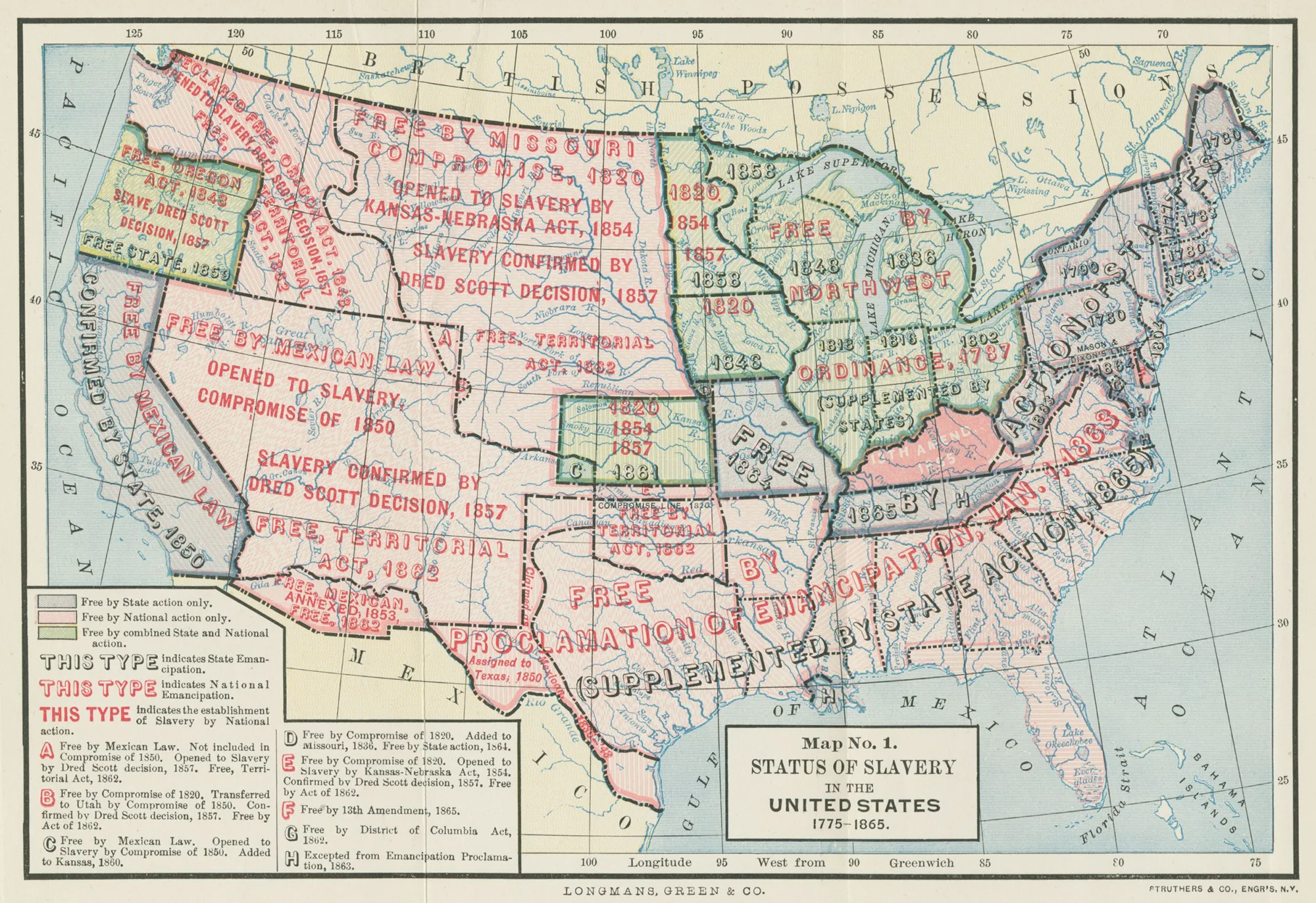

"In its 1857 decision that stunned the nation, the United States Supreme Court upheld slavery in United States territories, denied the legality of black citizenship in America, and declared the Missouri Compromise to be unconstitutional." — Missouri State Archives

The landmark ruling of Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857 exposed America's entrenched racial divisions and illustrated how the legal system was used to reinforce the country's racial caste system. Dred Scott was an enslaved man who, after living in the free territories of Illinois and Wisconsin where slavery was prohibited, sued in an attempt to gain freedom for himself and his family.

The Supreme Court rejected his suit in a 7-2 decision declaring that he had no right to bring it in the first place as Black people were excluded from being American citizens under the Constitution and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's majority opinion stated that Black people were "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." This landmark decision helped inflame conflicts over slavery between northern and southern states, which would explode into Civil War a few years later.

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. (1893). Status of slavery in the United States, 1775-1865

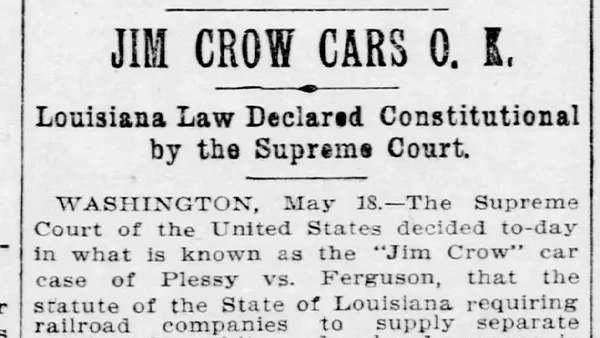

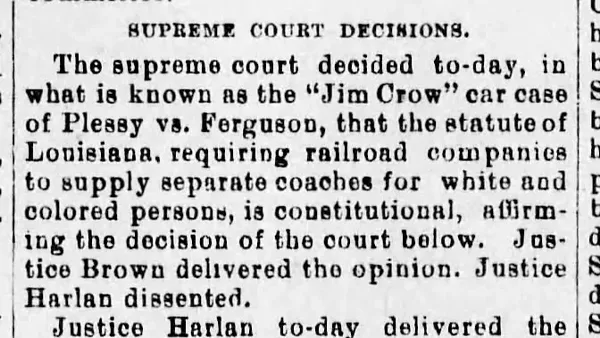

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

One pivotal moment that highlights the intricacies of race relations in America is the 1896 Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which established that racial segregation was constitutional as long as facilities were "equal." This decision, upholding a Louisiana law segregating train cars, established the right of states to enforce segregation. The ruling sanctioned a caste system where racial separation permeated schools, transportation, public accommodations and other aspects of daily life. It formed the legal basis for Jim Crow laws in the United States.

The lone dissenting opinion came from Justice John Marshall Harlan who disagreed that the law should be upheld, stating, "In view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law."

Today, the legacy of Plessy v. Ferguson can still be felt in the economic and educational disparities caused by decades of legal segregation.

In re Halladjian (1909)

"In In re Halladjian (1909), Armenians were declared white and made eligible for citizenship. The decision was based largely upon “scientific evidence” presented during the trial that equated their Caucasian origins with whiteness. But, during the early 1920s a significant shift in judicial interpretations of naturalization law led to a reevaluation of Armenian status. In Ozawa v. United States (1922) and in United States v. Thind (1923), the courts denied citizenship to Japanese and Asian Indian applicants based on the belief that “common knowledge” in the United States held them to be Asian, not white." — Oregon History Project

Jacob Halladijian was one of four Armenians who had his petition for American citizenship approved in a 1909 decision by a Boston circuit judge. In qualifying the men for citizenship, the judge noted that "all were white persons in appearance, not darker in complexion than some persons of north European descent traceable for generations. Their complexion was lighter than that of many south Italians and Portuguese."

The Naturalization Act of 1790 set up the first set of rules for U.S. citizenship, limiting citizenship to "any Alien being a free white person," which notably excluded all Asian people. However, the ability for Armenians to "appear" white granted them a legal advantage over other Asian immigrants to America.

The specific designation of Armenians as "white" in America would be codified shortly after in United States v. Cartozian (1925), another case involving an Armenian appealing his rejected naturalization. The ruling declared, "It may be confidently affirmed that the Armenians are white persons, and moreover that they readily amalgamate with the European and white races."

Additional Reading:

Becoming White: Contested History, Armenian American Women and Racialized Bodies

Image Source: The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon · Monday, July 27, 1925

DOW V. UNITED STATES (1914)

“In 1914, before the 1952 Naturalization Act, the lower courts of the United States actually contested whether Jesus would be considered white enough to become a U.S. Citizen. In Dow vs. The United States, George Dow, a Syrian immigrant, argued that given Syria and the Middle East’s connection with Christianity and Judaism, the courts should allow him to be white in order to become a citizen." — Twitter Thread by Andres Villatoro, University of Pennsylvania

“Adaptation to life in America was fraught with tension and anxiety. The Dow vs the United States court case underlines an ambiguous position Syrians found themselves in at the start of the twentieth century. George Dow, a Maronite Christian and immigrant from north Lebanon launched legal action after his naturalisation leading to citizenship was denied in 1914. The problem George Dow and other Syrian immigrants had was there was a sense of confusion on how to racially classify them. The 1790 naturalization act officially racialized citizenship in the United States, stating any foreign-born resident needed to be white and free-born, i.e. not a slave, to have the right to American nationality.

At the heart of the issue was tension between the so-called scientific understanding of race vs common wisdom approaches to it. Dow mounted his case based on the racial science pervasive in his day, which essentially classified Semites as white, based on the works of German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840). Blumenbach wrote, “Modern Syrians are mixed Syrians, Arabians, and even Jewish blood. They belong to the Semitic branch of the Caucasian race, thus differ widely from their rulers, the Turks, who are in origin Mongolian.” However, the judges took the view that it was common sense that white in the 1790 act meant European, and thus George Dow did not qualify. It was Dow’s appeal to the Court of Appeals in 1915 that would see him get citizenship. The Appeals Court accepted the scientific definition offered by Dow’s defence, and the case would enable Arab Christians to become US citizens, but not Muslims.

Despite ‘becoming white’ legally, as Sarah Gualtieri writes, socially Syrians were still seen as somewhere between Asian and Black long after the court victory. Syrians lived in precarious positions and were seen as an in-between group. Charlotte Karem Albrecht makes the point that racially being Syrian was not based on who they were, but on how they related to blackness and other non-white groups. The first Arab Muslim would not gain the legal right to be naturalized until the 1940s, thus the 1915 case would divide Arab immigrants along the lines of religion.” Source: The New Arab

Ozawa v. United States (1922)

What does it mean to be "white" in the United States? Takao Ozawa was a Japanese immigrant who challenged the definition of a "free white person" after applying for citizenship in Hawaii in 1914. He had lived in the States for twenty years, was Christian and spoke English, but was denied on the grounds that he was ineligible as a Japanese person. In the Supreme Court ruling against Ozawa, Justice Sutherland argued that people considered white should be "confined to persons of the Caucasian Race."

Source: PBS Voices

United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923)

Only a year after Ozawa v. United States, Justice Sutherland further amended his own opinion in order to deny citizenship to a man named Bhagat Singh Thind. Thind, an immigrant from India, had been granted citizenship in the state of Oregon. However, a naturalization examiner appealed the Oregon District Court decision on the grounds that he was not white.

The case went to the Supreme Court, where Thind claimed that he was of "high-caste Hindu stock, born in Punjab, one of the extreme northwestern districts of India, and classified by certain scientific authorities as of the Caucasian or Aryan race." The Court nonetheless revoked his citizenship, with Sutherland writing that the phrase "free white person" was in fact only "synonymous with the word 'Caucasian' only as that word is popularly understood." Effectively, individuals must have white skin in addition to white, European heritage in order to gain citizenship.

Source: PBS Voices

Salvador Roldan v. LA County (1933)

"Since 1880, California Civil Code Section 60 had prohibited marriages between white persons and "Negros", "mulattos", or "Mongolians", but there was confusion over whether Filipinos were part of that last category." — APA Legal

Salvador Roldan, a Filipino American man, was denied a marriage license to his white wife, Marjorie Rogers; he contended that Filipinos should be categorized as "Malayan" rather than "Mongolian," allowing them to intermarry with white people. The court decided in his favor, determining that Filipinos should be classified as "Malayans."

However, the decision sparked backlash. "When word went out that a Filipino man was trying to marry a white woman in a case that could potentially prevail before the state Supreme Court, California lawmakers scrambled to change the law. In March 1933, the state senate passed two bills: one added "Malay" to the list of racial categories in the law banning interracial marriages, and another invalidated all marriages between whites and nonwhites. The state assembly approved the bills a month later. Only one assembly member voted against them — Frederick Roberts, the first Black member of the California legislature. The bills were quickly signed into law by California Governor James Rolph." —San Francisco Examiner

Mendez v. Westminster (1946)

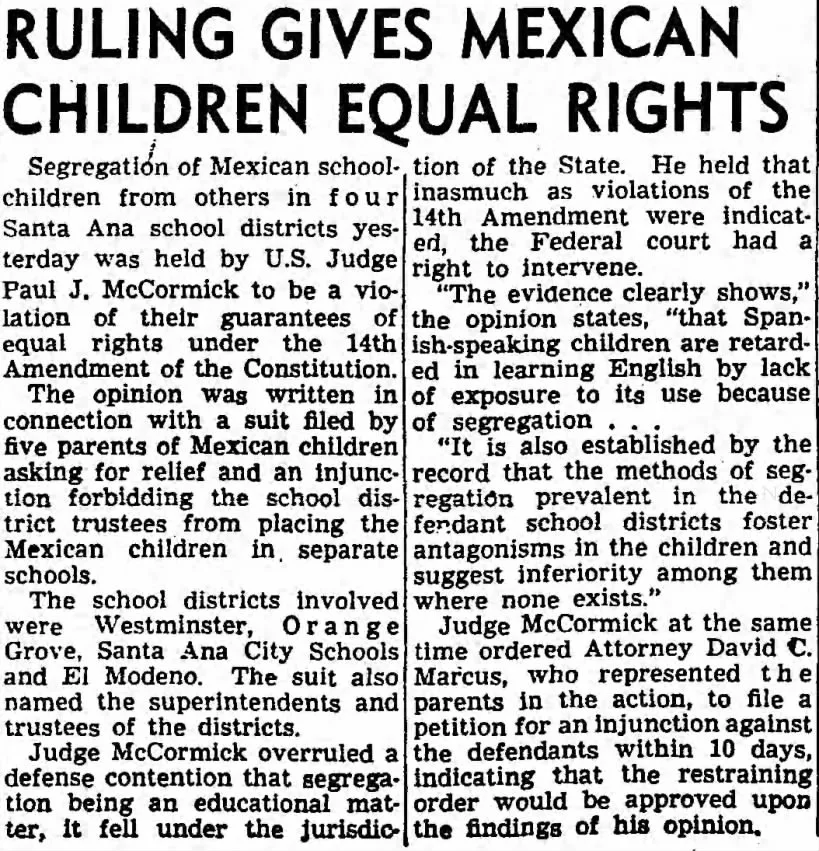

Eight years before Brown v. Board of Education, the case of nine-year-old Sylvia Mendez's rejection from a white school in California laid the groundwork for ending school segregation at the federal level. In an unconventional approach, the lawyers representing the Mendez family based their argument on social science, noting the ways in which segregation had a negative impact on the self-esteem of students at the local "School for Mexicans" where Mendez was to be sent. Students were even asked to take the stand and testify to their feelings of inferiority, feelings that were tragically shared by the adults responsible for their education: James Kent, the superintendent of one of the defending districts, stated that "people of Mexican descent were intellectually, culturally, and morally inferior to European Americans."

The Ninth District Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Mendez family, embracing their argument that segregation was discriminatory to Mexican-American students.

Los Angeles Times headline announcing the Mendez v. Westminster ruling. Source: Los Angeles Times, February 19, 1946. Accessed through online newspaper archive https://www.newspapers.com/article/7506969/the-los-angeles-times/

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

"All nine justices stood behind the opinion of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who declared, and I quote, “The doctrine of separate but equal has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

— John Shattuck

Brown vs. Board of Education was a momentous legal case that emerged from Topeka, Kansas, and played a crucial role in advancing the civil rights movement. The catalyst was the experience of Linda Brown, whose father, Oliver Brown, contested her requirement to travel to a distant segregated school instead of attending a nearby white school. Challenging the Topeka Board of Education's decision, this Supreme Court ruling made school segregation unconstitutional and directly confronted the false doctrine of "separate but equal" put forth in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Even with the law behind it, the actual integration of schools encountered significant opposition, particularly in Southern states. Progress was gradual, and despite the court's ruling, segregation persisted due to a variety of factors.

Loving v. Virginia (1967)

"'What are you doing in bed with this woman?' Sheriff R Garnett Brooks asked as he shone his flashlight on a couple in bed. It was 2 a.m. on July 11, 1958, and the couple in question, Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter, had been married for five weeks. 'I’m his wife,' Mildred responded." — History.com

After being legally married in Washington D.C., Richard and Mildred Loving returned home to Virginia, where they found themselves indicted under the state's laws against interracial marriage. The sentencing judge, Leon M. Bazile, claimed: "Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix." After their conviction, they took their case to the Supreme Court in the landmark case Loving v. Virginia (1967). The Court's unanimous decision struck down all remaining anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, deeming them unconstitutional and affirming the right to marry across racial lines.

Video Credit: HISTORY

University of California v. Bakke (1978)

Allan P. Bakke, a white former Marine, was rejected twice from the University of California Medical School, in part due to his age—Bakke was 33 at the time of his first application. After receiving a second rejection, Bakke sued the university. He alleged that the school's affirmative action program led to his denial based on his race, arguing reverse discrimination. While the court ruled that the use of strict racial quotas in admissions was unconstitutional, it also upheld affirmative action, stating that race could be considered as one of several factors in the admissions process. In a split decision, the court ordered the school to admit Bakke.

Students, under a Young Socialist Alliance banner, march in protest over the Supreme Court case Regents of the University of California vs. Bakke. Photographed by Leslie Ringold. University of Wisconsin Madison Libraries. https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AQLUFGJ4KAKLTR8B

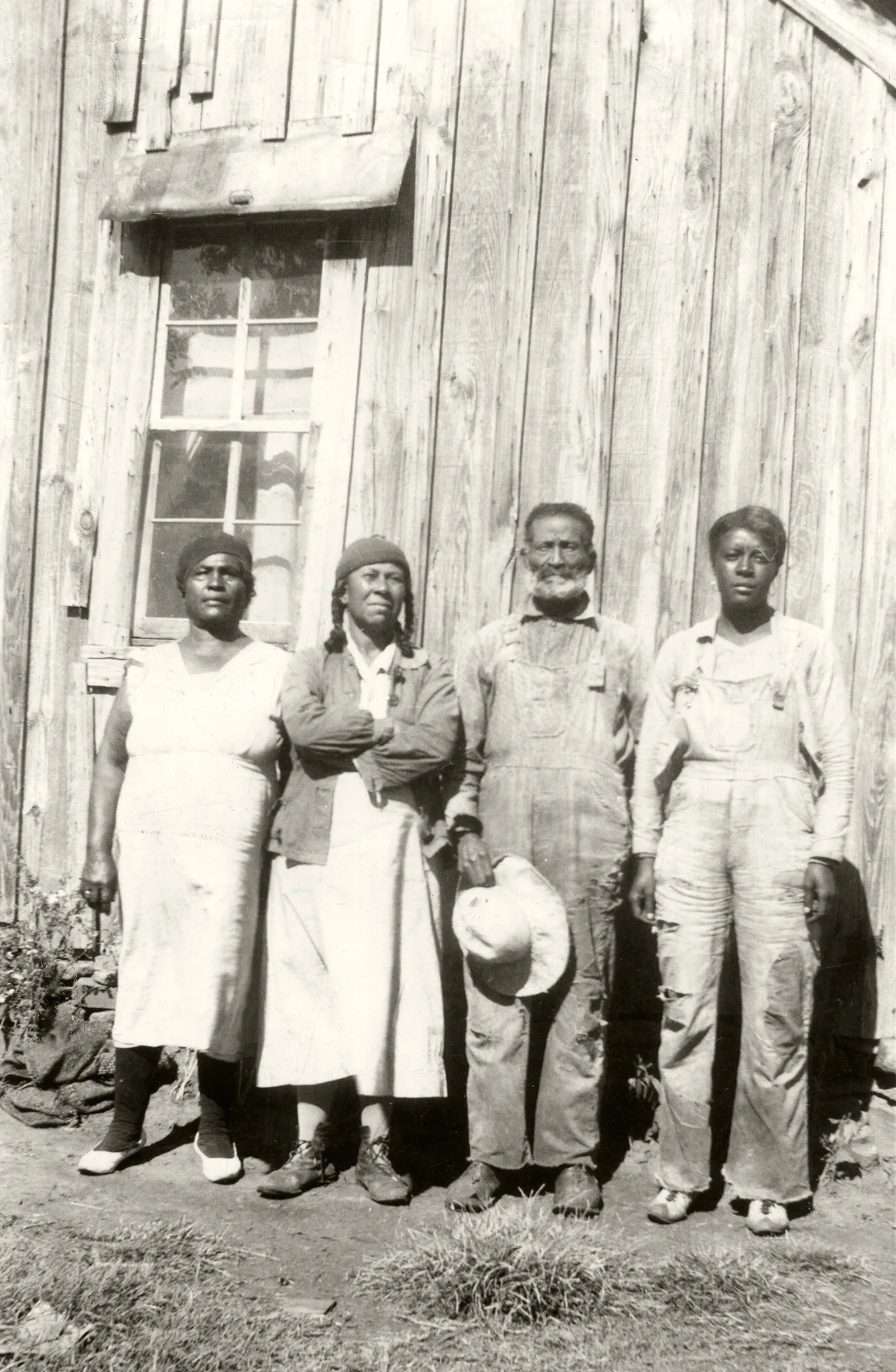

Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al. and Marilyn Vann et al. (2017)

"From the time she was a little girl, Marilyn Vann knew she was Black and she was Cherokee. But when she applied for citizenship in the Cherokee Nation as an adult, she was denied." — The Atlantic

The Cherokee Freedmen were descendants of enslaved individuals owned by Cherokee citizens. While citizenship rights were originally established after the Civil War in the Treaty of 1866, the idea of blood quantum was introduced by the federal government to determine eligibility for tribal citizenship through the degree of a person's Native American ancestry. Marilyn Vann and other descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen sued the Cherokee Nation to be admitted as tribal citizens. After a prolonged legal battle, the court ruled in 2017 that Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants deserved citizenship and voting rights under the 1866 treaty, highlighting identity, tribal sovereignty and historical justice concerns and sparking broader discussions about historical agreements' legal relevance and tribal citizenship criteria.

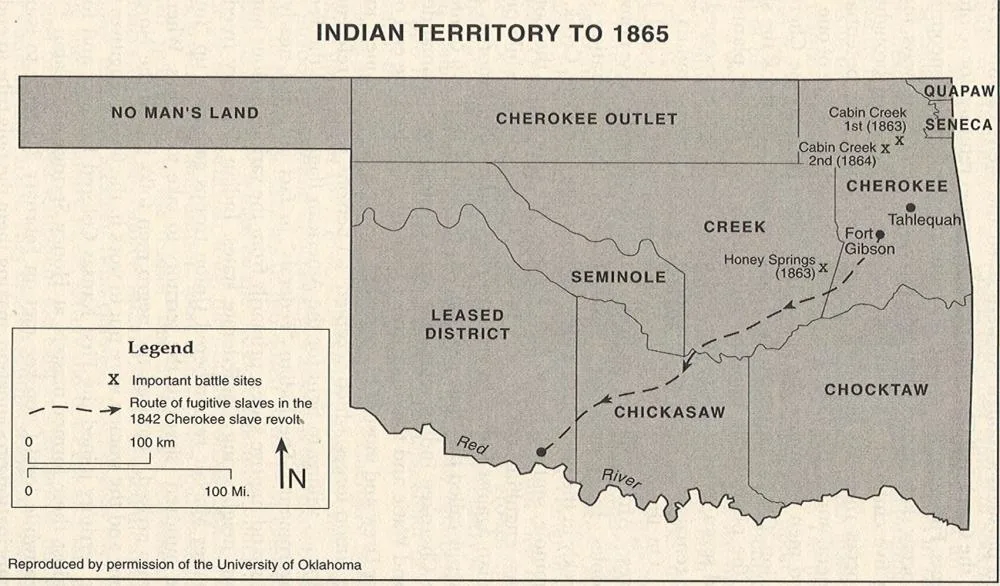

Maps of Native American Territory before and after the Civil War. Map traces the route of Cherokee fugitive slaves. Map originally from the University of Oklahoma Western History Collection, adapted by Quintard Taylor.

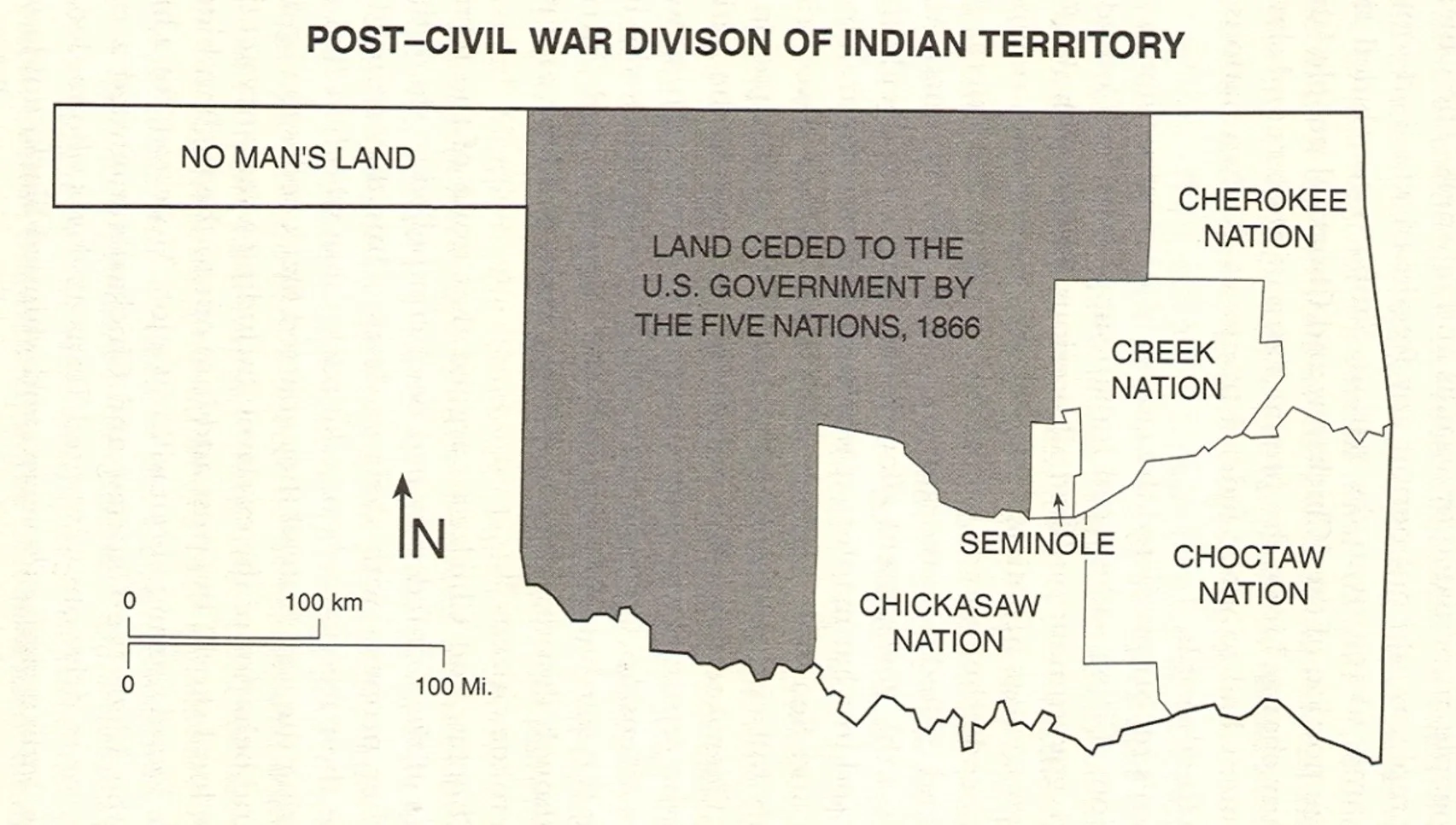

Maps of Native American Territory before and after the Civil War. Map shows land ceded in treaties like the Treaty of 1866, which ensured citizenship for Cherokee Freedmen. Maps originally from the University of Oklahoma Western History Collection, adapted by Quintard Taylor.

HENRY ET AL. V. NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE ET AL. (2020)

As recently as late 2020 to early 2021, the National Football League (NFL) used a discriminatory policy called “race-norming.” The policy presumed Black players function at a lower cognitive level than white players. As such, Black players who suffered a traumatic brain injury were determined to be eligible for less pay than their white counterparts.

The NFL used this policy from 2017 until 2020 to justify a lower payout for retired Black players who submitted brain injury-related insurance claims. The NFL used racial cognitive norms to determine which players were eligible for payouts. This is how the NFL calculated how much it should award a player as compensation for traumatic brain injuries. Dementia testing falls under the umbrella of the NFL’s concussion settlement, which guarantees retired players the right to money based on head injuries caused by NFL play.

In 2017, following a billion-dollar lawsuit related to traumatic brain injuries, the league was allowed to use race-norming as a way to determine how much compensation was due to the injured former players named in the suit. In 2020, former NFL players Najeh Davenport and Kevin Henry filed a civil rights lawsuit that brought this practice to light. In 2021, the NFL and lawyers representing “thousands of retired NFL players” agreed to a settlement that would “end race-based adjustments in dementia testing,” reports the Associated Press. Still, lawyers assert that the settlement process cannot be fair until the NFL is fully transparent with how it handles demographic information.

Source: ABC News

Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, UNC (2023)

"There is no caste here." — Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, Plessy v Ferguson (1896)

In June 2023, the Supreme Court struck down the existing affirmative action programs implemented at Harvard and the University of North Carolina under pressure from conservative activists from the Students for Fair Admission. While affirmative action has historically been used to ensure fair considerations in school admissions for people of color, the court ruled 6-3 in the UNC case and 6-2 in the Harvard case that these programs are unconstitutional as they violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Both Harvard and UNC have released statements mentioning that they will comply with this decision. However, in their statement, both universities remain steadfast that their dedication to diversity is as important as their dedication to academic excellence.

Affirmative action: Supreme court hears arguments from UNC and Harvard | USA TODAY

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Why do you think individuals throughout history have sought legal recognition as ‘white’? What advantages might have been sought, and what does this say about racial hierarchies?

- How do these decisions impact individuals’ lives and their perception of their own racial identity?

- Do people sue to be called white outside of the United States? If so, where?

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Why do you think individuals throughout history have sought legal recognition as ‘white’? What advantages might have been sought, and what does this say about racial hierarchies?

- How do these decisions impact individuals’ lives and their perception of their own racial identity?

- Do people sue to be called white outside of the United States? If so, where?