Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

In this clip, Isabel gives an example of how caste shows up in India and also in Germany. Her example debunks the idea that caste is always based on race or ethnicity. In fact, she uses the story of manual scavengers and Nazi oppression to further drive home the fact that caste systems are rooted in dominance, with one group claiming a higher ranking in a society over others. “We have to consider oppression in a way that does not centralize race,” says Isabel.

In this module learners will see examples of how caste has shown up historically in both India and Germany, where caste systems are not inherently created by race.

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

In this clip, Isabel gives an example of how caste shows up in India and also in Germany. Her example debunks the idea that caste is always based on race or ethnicity. In fact, she uses the story of manual scavengers and Nazi oppression to further drive home the fact that caste systems are rooted in dominance, with one group claiming a higher ranking in a society over others. “We have to consider oppression in a way that does not centralize race,” says Isabel.

In this module learners will see examples of how caste has shown up historically in both India and Germany, where caste systems are not inherently created by race.

Who Do You Love?

“Endogamy is the only characteristic that is peculiar to caste, and if we succeed in showing how endogamy is maintained, we shall practically have proved the genesis and also the mechanism of caste.”

— Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development”

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

AUGUST AND IRMA

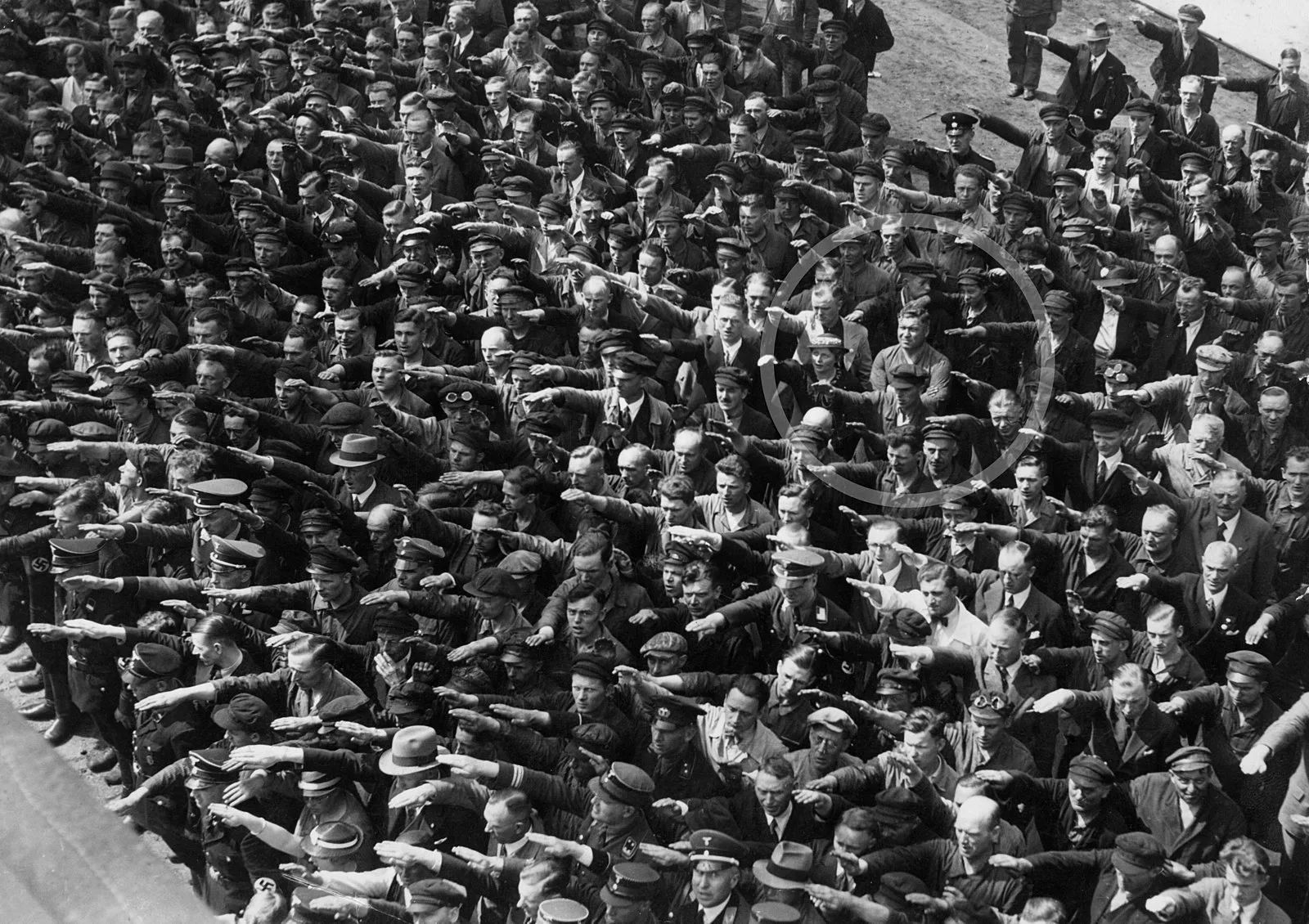

During the heat of the launch of a German army vessel in 1936, hundreds of men and women held their arms up high in salute and shouted their loudest “sieg heil” to show their undying allegiance to the Nazi Party. Among that crowd, a lone man stood with his arms crossed as an act of defiance of the party. That man was August Landmesser, a person who realized that his political affiliation was superficial when he fell in love with a Jewish woman, Irma Eckler.

Source: Rare Historical Photos

Germany’s Nuremberg Race Laws made their relationship illegal. “The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour was in effect, which stated that ‘Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if concluded abroad to circumvent this law’ (Article 1.1) and ‘extramarital relations between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden’ (Article 2.1),” writes journalist Nikola Budanovic.

The laws came into effect one month after Landmesser and Eckler’s daughter was born. The Nuremberg Laws forbade any relationship, including marriages, between Germans and Jews, therefore the two stayed unmarried.

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks | ORIGIN

Irma Eckler and August Landmesser, portrayed by Victoria Pedretti and Finn Wittrock in “ORIGIN”

ENDOGAMY IN INDIA

In making sense of how the caste hierarchy has sustained itself over centuries, it’s impossible not to turn to the institution of marriage. Noting the deep-rooted connection between caste and gender, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit scholar, reformer and Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the constitution for the future Republic of India noted in 1916, “Caste in India means an artificial chopping off of the population into fixed and definite units, each one prevented from fusing into another through the custom of endogamy.”

Endogamy refers to the custom of marrying within one’s own social group — in this case, within one’s own caste — and the prohibition on inter-caste marriage.

This unique interplay between patriarchy (a social system that prioritizes men over women) and Brahmanism creates rigid social trajectories for every member of society, a breach of which can result in ex-communication and ostracization or more extreme punitive measures, including harassment, murder and sexual violence.

However, it is necessary to nuance this discussion with the understanding that not all inter-caste marriages are necessarily treated the same. While inter-caste marriages between upper-caste men and marginalized women (hypergamy) are ostracized and participants are often subject to verbal and physical abuse, the worst violence is reserved for inter-caste marriages between upper-caste women and marginalized-caste men (hypogamy). Under Brahmanical patriarchy, women are considered to be “gateways,” or points of entry, into the caste system. Therefore, the “purity of blood” — an essential feature of the caste system — is institutionalized through strict, and often violent, control over women’s sexuality and relationships. In its worst manifestations, it takes the form of ‘honor killing,’ the killing of a relative, when women or men are perceived to have brought dishonor on their family.

Who Do You Love?

“Endogamy is the only characteristic that is peculiar to caste, and if we succeed in showing how endogamy is maintained, we shall practically have proved the genesis and also the mechanism of caste.”

— Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development”

“Endogamy is the only characteristic that is peculiar to caste, and if we succeed in showing how endogamy is maintained, we shall practically have proved the genesis and also the mechanism of caste.”

— Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development”

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks

AUGUST AND IRMA

During the heat of the launch of a German army vessel in 1936, hundreds of men and women held their arms up high in salute and shouted their loudest “sieg heil” to show their undying allegiance to the Nazi Party. Among that crowd, a lone man stood with his arms crossed as an act of defiance of the party. That man was August Landmesser, a person who realized that his political affiliation was superficial when he fell in love with a Jewish woman, Irma Eckler.

Source: Rare Historical Photos

Germany’s Nuremberg Race Laws made their relationship illegal. “The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour was in effect, which stated that “Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if concluded abroad to circumvent this law” (Article 1.1) and “extramarital relations between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden” (Article 2.1),” writes journalist Nikola Budanovic. “The laws came into force on the 15th of September, 1935. On October 29th, just one month later, Landmesser and Eckler’s daughter, Ingrid, was born. The Nuremberg Laws explicitly forbade any sort of relationship, let alone marriages, between Jews and Germans, so the couple remained unmarried.”

Courtesy of ARRAY Filmworks | ORIGIN

Irma Eckler and August Landmesser, portrayed by Victoria Pedretti and Finn Wittrock in “ORIGIN”

ENDOGAMY IN INDIA

In making sense of how the caste hierarchy has sustained itself over centuries, it’s impossible not to turn to the institution of marriage. Noting the deep-rooted connection between caste and gender, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit scholar, reformer and Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the constitution for the future Republic of India noted in 1916, “Caste in India means an artificial chopping off of the population into fixed and definite units, each one prevented from fusing into another through the custom of endogamy.”

Endogamy refers to the custom of marrying within one’s own social group — in this case, within one’s own caste — and the prohibition on inter-caste marriage.

This unique interplay between patriarchy (a social system that prioritizes men over women) and Brahmanism creates rigid social trajectories for every member of society, a breach of which can result in ex-communication and ostracization or more extreme punitive measures, including harassment, murder and sexual violence.

However, it is necessary to nuance this discussion with the understanding that not all inter-caste marriages are necessarily treated the same. While inter-caste marriages between upper-caste men and marginalized women (hypergamy) are ostracized and participants are often subject to verbal and physical abuse, the worst violence is reserved for inter-caste marriages between upper-caste women and marginalized-caste men (hypogamy). Under Brahmanical patriarchy, women are considered to be “gateways,” or points of entry, into the caste system. Therefore, the “purity of blood” — an essential feature of the caste system — is institutionalized through strict, and often violent, control over women’s sexuality and relationships. In its worst manifestations, it takes the form of ‘honor killing,’ the killing of a relative, when women or men are perceived to have brought dishonor on their family.

What’s In A Name?

“Last names are a deeply political category and sometimes carry a cruel history of oppression. In an article in The Atlantic, Edward Delman mentions some state-led programmes meant to create homogenous identities, such as Spanish colonisers dictating Filipinos’ surnames, and the Communist Bulgaria authorities deciding Turk and Bulgarian Muslims surnames in the 1980s. The surname history of the Jews living in Central and Eastern Europe depicts the power of the early modern states and dominant people controlling the lives of the marginalised using naming hierarchy. Joseph II, the ruler of the Habsburg empire, while granting Jews the same rights as Christians, asked them to strictly adopt German first names and family names in 1781. Nelly Weiss writes in “The Origin of Jewish Family Names” that Jews’ names were often decided by civic authorities, who chose the humiliating Kanalgeruch (sewer’s stink) and Ostertag (Easter). The state authorities, on their part, created surnames from plants’ names (Rosenzweig, Mandelbaum), stones (Steinberg, Steinmann), physical appearance (Gross, Lang, Kurz), and occupations (Koch, Schmied, Zimmermann). It was no surprise then that when Israel was founded, many Jews with humiliating and European-sounding names adopted Hebrew names.” — Amrita Ghosh and Arun Kumar, Scroll.in

In India, a person’s caste identity is coded into their last name. This goes back to ancient Hindu writings, which defined the caste hierarchy and included suggestions for caste-based surnames. Historians Amrita Ghosh and Arun Kumar write “last names are a deeply political category and sometimes carry a cruel history of oppression.” Asking for someone’s last name reveals their caste, and this seemingly subtle question has historically been used by upper castes to locate the caste of those with whom they’re conversing and insinuate their own upper-caste identity.

Given this, in some cultures, asking questions such as ‘What’s your last name?’ is far from innocuous and perpetuates casteist systems of segregation and othering.

Photo Credit: “ORIGIN”

Photo Credit: “ORIGIN”

How Do You Worship?

“What festivals do you celebrate?”

“Does your family go to the temple often?”

“Which God(s) do you pray to?”

“What religion do you practice?”

How Do You Worship?

“What festivals do you celebrate?”

“Does your family go to the temple often?”

“Which God(s) do you pray to?”

“What religion do you practice?”

These are some examples of questions that can be used to socially locate people within the caste hierarchy in India. Given that caste finds its origins and sanction in religious scripture, it is not uncommon for members of these communities to change their religion as a step towards liberating themselves and as an act of rebellion against caste supremacy. Dr. Rahul Sonpimple, a Dalit activist, explains, “There is a long-standing history of conversion of Hindu Dalits to other religions in various states of India. Dalits have been converting to Christianity and other anti-brahminical sects like Kabir Panth for a very long time. And in contemporary times, conversions into Buddhism and Islam became common among Dalits thanks to the efforts of organised movements that seek to counter caste discrimination.”

According to a 2021 Pew Survey, nearly 9 in 10 Buddhists in India are Dalits, and a quarter of Christians identified as Scheduled Tribes, the official term for the Dalit caste. Asking probing questions about people’s religious beliefs, even in the context of getting to know each other, can touch upon significant aspects of social identity that help place individuals within societal hierarchies.

PAUSE AND REFLECT

Is there a relationship between religion and social identity in your community? If so, is it similar or different from the context described in India?

PAUSE AND REFLECT

Is there a relationship between religion and social identity in your community? If so, is it similar or different from the context described in India?

ACTIVITY

Caste on the Menu: Exploring the Intersection of Caste and Cuisine in India

“What social media fails to understand is that caste is ingrained in our taste buds and eating habits. Food snobbery is a part of India and the food that belongs to upper castes has always been more celebrated.”

— Parul Agrawal, The Quint

Indian author Sujatha Gidla explains how caste identification occurs within her country:

Photo Credit: “ORIGIN”

Photo Credit: “ORIGIN”

“In Indian villages and towns, everyone knows everyone else. Each caste has its own special role and its own place to live. The Brahmins (who perform priestly functions), the potters, the blacksmiths, the carpenters, the washer people and so on — they each have their own separate place to live within the village. The Untouchables, whose special role is to labor in the fields of others or to do other work that Hindu society considers filthy, are not allowed to live in the village at all…

… If you are educated like me, if you don’t seem like a typical Untouchable, then you have a choice. You can tell the truth and be ostracized, ridiculed, harassed — even driven to suicide, as happens regularly in universities. Or you can lie. If they don’t believe you, they will try to find out your true caste some other way. They may ask you certain questions: “Did your brother ride a horse at his wedding? Did his wife wear a red sari or a white sari? How does she wear her sari? Do you eat beef? Who is your family deity?” They may even seek the opinion of someone from your region.”

Photo Credit: “ORIGIN”

“In Indian villages and towns, everyone knows everyone else. Each caste has its own special role and its own place to live. The Brahmins (who perform priestly functions), the potters, the blacksmiths, the carpenters, the washer people and so on — they each have their own separate place to live within the village. The Untouchables, whose special role is to labor in the fields of others or to do other work that Hindu society considers filthy, are not allowed to live in the village at all…

… If you are educated like me, if you don’t seem like a typical Untouchable, then you have a choice. You can tell the truth and be ostracized, ridiculed, harassed — even driven to suicide, as happens regularly in universities. Or you can lie. If they don’t believe you, they will try to find out your true caste some other way. They may ask you certain questions: “Did your brother ride a horse at his wedding? Did his wife wear a red sari or a white sari? How does she wear her sari? Do you eat beef? Who is your family deity?” They may even seek the opinion of someone from your region.”

In order to begin exploring caste-based privilege, we can start by thinking about the questions and language we use to consciously or subconsciously locate each other in the caste hierarchy.

PAUSE AND REFLECT

When you tune in to your local news channel, do you notice how people from different parts of town or different backgrounds are shown? Can you spot any patterns or trends in how people who might be richer or poorer, or from different cultures, are talked about or presented? What do you think this might say about how your community sees these different groups?

PAUSE AND REFLECT

When you tune in to your local news channel, do you notice how people from different parts of town or different backgrounds are shown? Can you spot any patterns or trends in how people who might be richer or poorer, or from different cultures, are talked about or presented? What do you think this might say about how your community sees these different groups?